I’d like to take this opportunity to take a look at a lesser known variation of the run and shoot.

Hemlock, another contributor on this site, has fantastic insight into the Mouse/Jenkins/Jones version of the Run and Shoot that found it’s way into the NFL level in the early 90’s. The origins of that version of Run and Shoot, however, not only looked different in terms of plays and philosophy of attack, but also had a lesser known evolutionary branch that was basically limited to the Midwest United States, especially Indiana.

Glenn “Tiger” Ellison’s book should be required reading for all coaches, if for nothing else then the beginnings of the book where he talks about how he came to develop (truly create) an offense. More importantly, it details how his “coaching epiphany” allowed him to break out of the monotony of the generic offense and football philosophy which surrounded him.

(For the purists, forgive my shortened paraphrase)

Ellison was a coach at Middletown High School in Ohio, and it 1958 he found himself staring down a 1-4 record. Like Ohio State, under the guidance of Woody Hayes at the time, most high school teams relied on the “3 yards and a cloud of dust” approach. When things weren’t working, the players and coaches simply had to try harder. As Ellison noted, the idea was if the coaching staff and the 11 offensive players poured every ounce of themselves into the play, they could WILL themselves to at least 3 yards. This is a great thought. However, when you fail (and in competitive sport, there is always a loser), your failure is attributed to either your laziness, your inability to motivate, or both.

Ellison, like many football coaches, found himself putting more pressure on his staff, who put more pressure on the players, who in turn saw their execution and confidence falter.

It was during a trip to the park, probably to wonder about his job security, that Ellison had his epiphany. There, a group of kids were playing a pickup game of 2-hand touch football. Ellison watched as the QB, throwing on the run, would release the football to a receiver breaking toward grass. There was no diagram, no play call to follow, just “run out there and get open”.

I’d like to take a timeout to talk about Bob Gibson. Yeah, I know, way out of left field (no pun intended), but please bear with me.

In 1968, Bob Gibson had an ERA of 1.12, which is a record for the live ball era, and was just off the MLB record of .96 set during the dead ball era. Gibson was so dominant that after the 1968 season, MLB lowered the pitcher’s mound from 15 to 10 inches to give hitters a fighting chance.

During one game in the 68’ season, Bob gave up a single to the opposing pitcher, who was a notoriously bad batter. When asked by a reporter how he managed a hit off baseball’s most dominant hurler, the pitcher replied: “I closed my eyes, and I swung like hell!”

That, is exactly what Ellison started to do with his team at Middletown.

From the micro-managing, ultra-conservative, fist pounding coach came this new philosophy:

1.) Go reckless!

2.) Stay loose!

3.) Score now!

Practices became laid back. If it wasn’t fun, why were we doing it? Instead of detailing the quarterback’s mechanics and the receiver’s route stem and break, the coaching point became “you run out there, he’ll get open, and you throw it”.

Ellison spent the rest of that year operating out of the lonesome polecat, winning his remaining games. The following season, he add a little more systemization and developed a double wide, double slot set that is so recognizable as “Run and Shoot” today. It is important to realize that while he did add some structure to his offense, he now approached his problems from a pragmatic point of view, rather than a tacit, “this is the way we’ve always done it”/”everyone else does it this way” approach. The greatest minds in any field think this way. Anyway, he went on to be wildly successful, and even became an assistant for Woody Hayes at Ohio State.

Another quick aside: One of Ellison’s most prolific passing concepts was “Gangster”, which began by motioning into trips (which started the idea of using motion to identify coverage). Gangster was the grandfather of our modern day Go route, and basically looked like a flood route with the “deep out” guy simply finding grass.

The quarterback would roll right with the FB blocking and throw on the run. Ellison also gave his quarterback the unheard of freedom to roll the opposite way whenever he felt like it to throw what was essentially the choice route. Very cool.

Two coaches picked up on the basic structure and philosophy of Ellison. The first one you all know about. The second was a head coach at small private school in southern Indiana called Franklin College. His name was Stewart “Red” Faught. Facing limited scholarships, limited staff, and limited, well, just about everything else, Coach Faught knew trying to win the old way would not work. He needed an edge, and he found it in the animal Ellison created.

The main difference between Mouse’s version and Red’s version of the run and shoot lay not only in route structure, but in the philosophy of attack. Make no mistake, Red was shocking the folks in Indiana with how much he was throwing the football. Coach Faught said when the quarterback got off the bus he wanted the ball in the air until he got back on. One of my favorite Redism is: “Balance?! Hell, pass!”

However, Red’s version did include some wing-T run game elements whose primary function was to set up one of the most devastating Play Action Passing and Play Action Screen games ever devised. More than once, I’ve heard coaches who really knew him say he ran just enough for you to believe the play fakes.

Red’s run game included some base inside runs, and as expected, the draw. Later on, Red would become the offensive coordinator at Georgetown College (which, despite the fact they had several more scholarships, Red held a winning record against while at Franklin) and he added some triple option, setting the foundation for Georgetown to win the 2000 and 2001 NAIA national championship.

For the purposes of this article, I want to focus on his sweep and trap series. For those versed in the “fun” terminology that Ellison created, that would be “Texas” and “Popcorn”.

One of the improvements Red made to the run and shoot was use of Rocket Sweep. Ellison’s version utilized a orbit sweep with the FB leading off the edge. As early as the 1970’s Franklin College was running the Rocket, and few teams could keep up. Anyone who hasn’t checked out Ted Seay’s Wild Bunch manual needs to do so right now for the best explanation I’ve heard for the power of the Rocket Sweep.

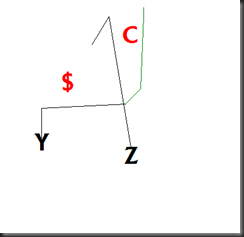

While not from the same formation, this is the best diagram of Rocket Sweep I could find on Google…..and I did spend over 30 seconds looking.

The slot, sent in deep motion, should be behind the FB when the ball is snapped. The QB reverses out and pitches. The slot should catch the ball just as he is breaking the tackle box. Because they will never make a play, every down lineman inside a 5 technique can be left unblocked (many times, the 5 tech can’t make a play either and can be ignored), allowing offensive linemen to scramble to the second and third level.

The sweet part of rocket how it demands that the defense move pre-snap, because after we snap the ball you will be out of position. Obviously, like any sweep, you stop the Rocket by keeping contain and making the runner cut back into the defensive pursuit. It is the pursuit that sets up the constraint play known as “Popcorn” (trap).

Before we get into trap let’s examine a current trend in the NFL. Pre-inside zone, any team worth their salt stopped trap. Trap, power and power sweep were the basis of the NFL run game. Then, people started to pass and utilize area blocking. The demands on an Over Front 3 technique started to shift into a more penetrating, rush the passer, split the zone double type of player. The Warren Sapp’s of the world became gold. In the last few years, however, you can see a cyclical return to the use of trap as a constraint play, and NFL teams are garnering big yards. The Rocket Sweep and the roll-out pass game Red utilized lends itself to horizontal and vertical DL movement, and the trap take perfect advantage.

Again, bear with the diagram.

The left slot goes in Rocket motion to the right, and the QB opens up to his left (which is the same as if he were reversing out to pitch the sweep), and hands to the FB running trap to the right.

As we mentioned, this little series had the power to make defenses worry about the width of the field, and then make them pay when they rallied too strongly to the sweep. The real beauty, and what Red loved to do, was the Play Action Passes and Screens off this action.

To wrap up this article, we will look at Red’s best play action pass (Popcorn Pass), and then some of the screens he would throw off it.

Rocket motion, fake the trap, and boot to the smash route. Very much like an inverted Buck waggle. This was a simple play, yet with defensive secondary concerned with filling the alley on Rocket, it was a highly productive part of the playbook.

Another important difference between Mouse and Red was in protection. On Popcorn Pass, 7 blockers stayed in. Red also had an 8-man protection call “Everybody Block” (love it). With the ability to utilize more than just the 6-man protection Mouse and his heirs utilize, Red was not merely providing more protection for his quarterback, he was preparing to ATTACK the blitz.

The Superback screen in Mouse’s version of the run and shoot is deadly. One of those ‘just when you think you have everything covered’ type of plays. Everything looks like roll-out (60/61 protection), and then the OL releases up field and the FB curls around for the dump off screen. It is just so easy to discount a skill player staying in to pass protect.

That’s right, I went there……

What Red added was the ability to manufacture multiple screen looks (off roll and play action), using multiple screen men (FB and slots), while keeping it simple with one screen scheme (the OL just had ‘screen left’ and ‘screen right’). Again, it is so easy to ignore an offensive skill player tied up in protection, especially with so many moving pieces (rocket, trap, play action pass) going on around you.

In the Popcorn Pass diagram, you can see how easy it would be to slip screen the FB to the left, and also how easy it would be to slip screen the slot who stayed in to block to the right. Some of the biggest gainers in Franklin College history have come off simple dump offs to a screen man with a wall of undersized, but willing to cut block their grandmother down, offensive linemen in front.

I’m not advocating one style of run and shoot over the other. However, I cut my teeth on Red’s run and shoot attack; the offense and the man holds a special place in my heart.

Red Faught passed away during my sophomore season at Franklin College. I, along with 90 other players, attended his funeral in our game jerseys….each of us also wore a plain red baseball cap. Red always wore one on the sidelines, despite the fact Franklin’s school colors are blue and gold (I loved that about him). Obviously, that is why people called him “Red”. I had the pleasure of speaking to him a few times, and that philosophy to “go reckless and stay loose” (which Ellison coined and Red so ardently advocated) applies as much to football as it does life.

“Balance?! Hell, pass!”

Right on Coach Faught, right on.