more at NZONE Offensive Systems

Showing posts with label Noel Mazzone. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Noel Mazzone. Show all posts

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Sunday, September 9, 2012

College Football Y'all

Hope you got a chance to catch some of the quality college football match-ups this weekend. I found a few

observations worth mentioning from some of the Air Raid patriarchs.

Mike Leach – I haven’t

paid much attention to Leach this spring/summer, opting to rather wait and see

how things played out in the fall before offering any editorial. It appears as though he is picking up right

where he left off from a philosophy standpoint (wide splits, vertical attack

focus). On one of WSU’s first explosive

plays featured an effective smash adjustment into the boundary, converting #1’s

hitch into a post once the split-safety widens to match the (corner) bend of

#2, leaving a middle-of-the-field void.

Noel Mazzone –

Like Leach, Mazzone is doing exactly as he had on his last stop; streamlined efficiency centered on horizontal stretch of perimeter defenders. Mazzone has

also adapted the Holgorsen, Franklin (TFS), 3-back change-up to capitalize on

defensive personnel adjustments. Similar to the two quarterbacks he had at ASU,

Mazzone’s UCLA quarterback, Brett Hundley, finished with a more than

respectable 75% completion ratio.

Tony Franklin – I

am really glad Hurricane Isaac delayed last week’s Louisiana Tech – Texas A&M

matchup until October 18, because it should allow enough time for a larger

viewing audience to develop an interest. There is plenty to

take note of with Tony Franklin’s offense, much of which we’ve previously written about. Of note are the

contributions of freshmen Tevin King and Kenneth Dixon who came out of nowhere

(plenty of depth with solid running backs) with over a 6 yard per carry average. Those are impressive stats, but I think it

also drives home Franklin’s aggressive style for playing offense.

Tech has incorporated more inside zone this

year and you may not find a team this year more adept at quick perimeter

screens (particularly solid, rocket/laser with linemen).

Of course, the one thing you can learn from Tech is how committed to tempo they are. They never move slower

than snapping within 20 seconds of the spot and when they operate in “attack”

tempo, no defense is safe. Even while leading with only 43 seconds left in the

first half and receiving to start the second half, Franklin still attempted to

work the clock and drive the field for points.

This style of play helped them break out of their own 1 yard line in the

third quarter and score on a 4 play drive.

“They’re going so fast there’s no time to explain what’s happening”– CBS Color commentator, Ron Zook, during the Louisiana Tech game broadcast

There is nothing "soft" or finesse about this brand of football. It is fast and nasty - both UCLA and La Tech relentlessly paced through 94

total offensive plays for over 600 yards total offense with over 250 yards

rushing and 5 TDs.

Here are two observations I felt like taking a look at.

Here are two observations I felt like taking a look at.

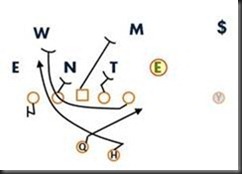

Fire (stretch read) with predetermined cutback

Fire (stretch read) with built-in option throw

Thursday, December 1, 2011

THE EDGES OF CONCISION

A couple of weeks back, just before the holiday, I was in Washington DC for another profoundly boring, tedious, and ultimately, pretentious academic conference. After giving my talk and fielding an hour or so of numbing questions I went to the hotel lounge to unwind with the help of my two best friends, Mr. Jameson and Mr. Glenfiddich. I was lucky that night because I managed to grab the TV before the fireplace and monopolize it – a good move indeed because the boors who eventually descended like locusts would undoubtedly not have wanted to watch something as stimulating as the game between Iowa State and Oklahoma State that fine evening. Now, no doubt because of the good company of my two aforementioned friends, I was just a bit distracted and unable to fully digest and appreciate what was unfolding in Ames that night, but I knew I had found something quite appealing to my oh so prosaic senses, especially when the Cyclones had the ball.

I got back the next day to Madison in time to watch another interesting match – that between Baylor and Oklahoma. And this is when, with the help this time of two other friends, Earl and Lady Grey, along with a healthy dose of lemon combined with a quick shot Ms. Brandy (muddled, of course), it all started to dawn on me, almost like the initial testament Joseph Smith experienced somewhere in New York state. It all began when one of the prophets, Matt Millen, declared in no uncertain terms that if Baylor wanted to be successful against OU that they needed to move RGIII around so as to change his launch points and prevent the Sooner D from teeing off on him. For a moment, I agreed with the prophet and considered myself, with bit of self-loathing, fortunate to be in a position to take in his divinatory powers. But then something happened: the game continued, Baylor continued, by and large, to keep RGIII in the same place, and eventually the Bears won.

That night I went back and watched the ISU-OSU tilt again and noticed the same thing; hardly any pocket movement. This jogged my memory a bit and sent me back to my Arizona State cutups, which brought my attention to something I had completely taken for granted at some level or another: none of these teams protect their QBs by changing their QBs’ launch points. Does that mean that they do not move the pocket? Of course not. Only that when they do so it’s primarily to isolate a single receiver on an easy throw, usually in a short yardage situation; in other words, when they move the QB it is not because they necessarily believe that it will help them protect him more effectively.

For anybody well-versed in the fundamentals of protection, this all seems counter-intuitive, right? I mean, after all, a stationary QB is a sitting duck just waiting to get blown apart by a defense that simply needs to stay in its lanes in order to bring their pressure home? How then do these teams do such a great job of protecting their QBs, especially when they are most of the time releasing not three, but four and five guys and are thus never protecting with any more than six people? If we pause to think about it for a second or two, the answer becomes self evident: all these teams secure their QBs by ensuring that the A and B gaps are always solid and by protecting their edges by way of their KEY screen games that come off of their inside zone schemes. Since Baylor, OSU, ISU, and ASU aggressively use their KEY games they are able to displace rushers and thus widen the edge thus increasing the distance a potential rusher must cover in order to get home. But this is only applicable if the defense continues to roll the dice, as it were, because the KEY game itself forces a defense to consider the potential costs and benefits of bringing such pressure.

This is yet another example of concision. By formulating and integrating packages so that they protect one another, not just the QB as a physical being, but concepts in and of themselves, they are able to reduce the number of things they need to carry in any given game. For all these teams, the KEY game along with whatever versions of ROSE and LINDA they run work to protect not only their respective 2 and 3 man SNAG games, but also their Shallow and Drive packages as well.

In a perverse sense then, protection is as much about the periphery as it is the center.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Mazzone Revisited

I wasn’t quite sure if we captured the premise of the Iowa State lesson of schematic concision well enough in the last post. Admittedly, it was an off-the-cuff editorial to a climactic match. I also wasn’t sure if we have done a complete enough job to date on stressing the simplicity of concepts within an offense (hemlock has tackled this exceptionally well in previous posts), particularly as it relates to Noel Mazzone this fall. Yes, we get that Arizona State has underperformed this season and Erickson will likely be gone at the end of this year (though it is a shame, considering how explosive their offense has been), but I don’t believe that discounts the value of learning what is working with Mazzone.

With this in mind and to serve as a type of sidebar edification on the matter, we’re “reposting” an exchange offered by hemlock and I on COACHHUEY (explaining Mazzone’s system). So not to break the flow of dialogue (or require any actual work on my part) I’m leaving the posts as-is in the sequence they occured . Hemlock’s thoughtful prose and profound commentary is in gold, while my rambling gibberish is in diarrhea green.

** I realize some of the video (through Vimeo) hosted here is hard to come by. If you are not aware of how to rip flash already, I’ll direct you to use Firefox and download the video add-on. Start a video, then enable the download (and its yours).

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

It IS zone-read, but its all controlled/filtered through a systematic way of horizontally stretching the defense, while at the core being vertically orientated (zone-read, F swing, Stick/Snag/Scat/Drive/Shallows/Verts/and tons of screens). There is an efficiency in his application (which is what we've been writing about) that is worth exploring (certainly doesn't carry near the amount of stuff Air Raid teams currently do). It isn't necessarily the plays themselves, but how they're packaged together and used as punch and counter-punch diagnosis.

How he teaches "the offense" is evident in what you've seen with Threet and Osweiller. They are lightening quick in throwing 3-step and 5-step that appears brutal on defenses (they know exactly what they are looking for based on the concept and process through it all).

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

Brophy and I are going to be writing more about the offense in weeks to come, but here are few things to keep in mind: Mazzone wants to stress the defense's perimeter fulcrum. Watch the USC game; I don't think I have ever scene such transparent objectives in my life; they are constantly trying to widen the defense. When they widen the edge their inside zone game become effective, but you need to remember that it's not a real rugged zone game; they don't do combos and stuff; its only effective if they have one on one matchups. But stretching the defense horizontally also helps his vertical game, because it transforms zone into man.

The thing to remember is this too: they really only carry a few concepts every game, especially in their dropback package. More later...

The thing to remember about their zone game is this: it's bang or bust; if they don't win their individual matchups the play goes no where. Think about some the idiotic comments that Rod Gilmore made the other night. It asked why on second and ten did Mazzone run what he described as an "inside handoff" that went for nothing. Well, it was the right call for the front; they had the numbers to win but simply did not on that play. I like to think of it as "scat" zone. I know that sounds odd, but it's not an inside zone in the Alex Gibbs, Eliot Uzelac sense.

In a lot of ways I think that Mazzone is reviving some old things that Purdue did once upon a time. Think of how he motions his backs; it reminds me of how Purdue, WAZZU, and for that matter Miami of yesterday all motioned to empty as a way of stretching the defense's flanks in order to create windows underneath, but also to put backers and backs on virtual islands.

Also, think of how they use the bubble. People talk about the bubble as an extended hand off, but most teams really do not throw it well enough for it to be considered their stretch or wide zone play; not the case with ASU. I don't think I've seen a team that can run bubbles with the back, from 2x2, or 3x1 as effectively as they do regardless of the look. In a sense, the bubble is one of their plays that they feel that they can run versus anything to make critical yards, regardless of whether the defense knows what coming or not. Their third scoring drive the other night that came of the Vontez's pick was built almost entirely of of bubbles in one form or another.

Chris is right, there is nothing radical about what their doing. We will cover this in a post later in the season, but the one thing that they have done better than just about anybody is to accelerate the speed of their vertical game; when their on their game they throw verticals just as fast as quicks.

Yeah, in a sense it really is just that - big on big; they never really get to the second level; basically, its the back's responsibility to make the backer miss, which is what happens when they get big plays out of their zone game.

In terms of packages they carry, if you watch them closely they basically run four concepts from 2x2 and 3x1: Snag; 4 Verts, Y Cross, and Drive or Shallow. Not a huge Smash team in the conventional sense; when they hit the corner its coming off their 3-man snag a lot.

That said, they do tag the backside with a number of different combos, such as double post, post corner, Dig choice, etc.

Its really about an Economy of Concepts

If you're horizontally stretching a defense and emptying the box (to run.....and run easy) I suppose it isn't necessary to mash and bang with getting vertical movement on IZ and working combos (still not sure if I swallow this just yet) them running IZ will blow your mind ("wtf are they doing!?!") if you're accustomed to how IZ is traditionally run out of 1 back.

watch how they 'zone' against a 3man front....not what you'd think

I would say that Alex Gibbs' one-cut rule is central to the success of the play in for Mazzone's back because of the nature of their scheme, which in part why the back aligns on the QB's heel rather than simply adjacent to him as he does in other zone gun schemes, such as Northwestern's, for example.

To build on Brophy's point, motion is used here in much the same way as it was used back in the day at Wyoming, Purdue, WAZZU, etc. Yes, it definately clarifies the read for the QB in that it tells him right away which side of the field he's going to work, especially in the Snag game, but it also is a way of putting extreme pressure on the number four to that side, the defense's fulcrum. It's another way of "controlling" this guy and making sure that he is out of the box, that he does not become a 1/5 player in the box.

Though most applications of ASU's offense are pretty basic in each game, the quirks against Oregon would be apparent for most coaches. Whereas most 7-man front defenses, Mazzone can pretty much give his quarterback a very clear picture. With Oregon's nickel/dime (2/1 DL) the picture was extremely cloudy with linebackers and safeties dropping into overhang positions. The heavy use of motion in that game was a product of getting Oregon to declare what they were truly running (where the safeties had to be.....and would the out-leverage themselves from helping their corners against the larger receivers). On the swing, it would primarily require the safety to make the stop because they were playing a heavy dose of C5 and rushing 4 or fire zoning and rushing 5.

What is interesting for coaches, was how Mazzone's system could adapt to it without losing it's shit. Facing something that was as different and that could get into and out of box threats pretty easy (from depth), ASU didn't have to do anything outside of themselves to handle it. With so many defenders outside the tackles on each snap, Oregon really was daring them to run inside and how ASU was hammering the flare/swing to open up the inside. If they threw the swing, it was going to have to be a safety to stop it (leaving X/Z pretty much 1-on-1) . I didn't find many times where Oregon didn't bring 5 every down, so it made the dig/shallow read pretty easy (either the WLB/MLB was widening for the swing or were both dropping to hook) .

What should be interesting for COACHES is not what they are doing but how they are processing the information on the field. Just by segmenting the defense, picking on one particular defender they can make some pretty safe assumptions on where everyone else will fit and who becomes the best ball carrier in that situation.

I think what we have to remember is that all spread offensive systems strive in some way or another to displace defenders and in the process place an inordinate amount of structural stress on the defense's force or alley players. Whether it's RichRod's spread option or Noel Mazzone's version, both offenses are really trying to hammer on a defenses adjuster backer, which in most 2 hi looks is going to be the sam, at least most of the time. RichRod does it with the Zone Read and Zone Bubble, as we've seen in the excellent talks that Brophy has posted on the blog. For Rich, it's really about trying to make sure that the adjuster never gets into the box, he's the guy they need to control. Mazzone too wishes to attack the adjuster, but his objectives are little different; yes, he wants to run inside zone, but, as Brophy noted, it's really more about identifying the defense's anchor player in order to diagnose not the scheme in general, but more importantly, the defense's individual matches, which, if you think about it, in the era of match-zone is more important than ever.

In a sense, it shows how motion is being used again not so much as a way of gaining mismatches and what not, the offense's general scheme already takes care of that, but of diagnosing what it is that the defense is doing. So, in a way, it just shows how we are coming full circle with the spread. Motion that was once jettisoned is now coming back as a tool for identifying a defenses seams and stress points.

Also, as was noted above, motion is not used blindly by Mazzone. In the Missouri game they hardly used motion because MU is fairly straightforward structurally; with Oregon, however, it was necessary.

With this in mind and to serve as a type of sidebar edification on the matter, we’re “reposting” an exchange offered by hemlock and I on COACHHUEY (explaining Mazzone’s system). So not to break the flow of dialogue (or require any actual work on my part) I’m leaving the posts as-is in the sequence they occured . Hemlock’s thoughtful prose and profound commentary is in gold, while my rambling gibberish is in diarrhea green.

** I realize some of the video (through Vimeo) hosted here is hard to come by. If you are not aware of how to rip flash already, I’ll direct you to use Firefox and download the video add-on. Start a video, then enable the download (and its yours).

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.It IS zone-read, but its all controlled/filtered through a systematic way of horizontally stretching the defense, while at the core being vertically orientated (zone-read, F swing, Stick/Snag/Scat/Drive/Shallows/Verts/and tons of screens). There is an efficiency in his application (which is what we've been writing about) that is worth exploring (certainly doesn't carry near the amount of stuff Air Raid teams currently do). It isn't necessarily the plays themselves, but how they're packaged together and used as punch and counter-punch diagnosis.

How he teaches "the offense" is evident in what you've seen with Threet and Osweiller. They are lightening quick in throwing 3-step and 5-step that appears brutal on defenses (they know exactly what they are looking for based on the concept and process through it all).

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.Brophy and I are going to be writing more about the offense in weeks to come, but here are few things to keep in mind: Mazzone wants to stress the defense's perimeter fulcrum. Watch the USC game; I don't think I have ever scene such transparent objectives in my life; they are constantly trying to widen the defense. When they widen the edge their inside zone game become effective, but you need to remember that it's not a real rugged zone game; they don't do combos and stuff; its only effective if they have one on one matchups. But stretching the defense horizontally also helps his vertical game, because it transforms zone into man.

The thing to remember is this too: they really only carry a few concepts every game, especially in their dropback package. More later...

The thing to remember about their zone game is this: it's bang or bust; if they don't win their individual matchups the play goes no where. Think about some the idiotic comments that Rod Gilmore made the other night. It asked why on second and ten did Mazzone run what he described as an "inside handoff" that went for nothing. Well, it was the right call for the front; they had the numbers to win but simply did not on that play. I like to think of it as "scat" zone. I know that sounds odd, but it's not an inside zone in the Alex Gibbs, Eliot Uzelac sense.

In a lot of ways I think that Mazzone is reviving some old things that Purdue did once upon a time. Think of how he motions his backs; it reminds me of how Purdue, WAZZU, and for that matter Miami of yesterday all motioned to empty as a way of stretching the defense's flanks in order to create windows underneath, but also to put backers and backs on virtual islands.

Also, think of how they use the bubble. People talk about the bubble as an extended hand off, but most teams really do not throw it well enough for it to be considered their stretch or wide zone play; not the case with ASU. I don't think I've seen a team that can run bubbles with the back, from 2x2, or 3x1 as effectively as they do regardless of the look. In a sense, the bubble is one of their plays that they feel that they can run versus anything to make critical yards, regardless of whether the defense knows what coming or not. Their third scoring drive the other night that came of the Vontez's pick was built almost entirely of of bubbles in one form or another.

Chris is right, there is nothing radical about what their doing. We will cover this in a post later in the season, but the one thing that they have done better than just about anybody is to accelerate the speed of their vertical game; when their on their game they throw verticals just as fast as quicks.

Yeah, in a sense it really is just that - big on big; they never really get to the second level; basically, its the back's responsibility to make the backer miss, which is what happens when they get big plays out of their zone game.

In terms of packages they carry, if you watch them closely they basically run four concepts from 2x2 and 3x1: Snag; 4 Verts, Y Cross, and Drive or Shallow. Not a huge Smash team in the conventional sense; when they hit the corner its coming off their 3-man snag a lot.

That said, they do tag the backside with a number of different combos, such as double post, post corner, Dig choice, etc.

Its really about an Economy of Concepts

If you're horizontally stretching a defense and emptying the box (to run.....and run easy) I suppose it isn't necessary to mash and bang with getting vertical movement on IZ and working combos (still not sure if I swallow this just yet) them running IZ will blow your mind ("wtf are they doing!?!") if you're accustomed to how IZ is traditionally run out of 1 back.

watch how they 'zone' against a 3man front....not what you'd think

I would say that Alex Gibbs' one-cut rule is central to the success of the play in for Mazzone's back because of the nature of their scheme, which in part why the back aligns on the QB's heel rather than simply adjacent to him as he does in other zone gun schemes, such as Northwestern's, for example.

Against Oregon, the ASU offense relied heavily on motioning the H or Z into the formation. They barely used motion against Missouri. It is only used to make a more decisive read for the throw (remove a defender from the running lane).

Though most applications of ASU's offense are pretty basic in each game, the quirks against Oregon would be apparent for most coaches. Whereas most 7-man front defenses, Mazzone can pretty much give his quarterback a very clear picture. With Oregon's nickel/dime (2/1 DL) the picture was extremely cloudy with linebackers and safeties dropping into overhang positions. The heavy use of motion in that game was a product of getting Oregon to declare what they were truly running (where the safeties had to be.....and would the out-leverage themselves from helping their corners against the larger receivers). On the swing, it would primarily require the safety to make the stop because they were playing a heavy dose of C5 and rushing 4 or fire zoning and rushing 5.

What is interesting for coaches, was how Mazzone's system could adapt to it without losing it's shit. Facing something that was as different and that could get into and out of box threats pretty easy (from depth), ASU didn't have to do anything outside of themselves to handle it. With so many defenders outside the tackles on each snap, Oregon really was daring them to run inside and how ASU was hammering the flare/swing to open up the inside. If they threw the swing, it was going to have to be a safety to stop it (leaving X/Z pretty much 1-on-1) . I didn't find many times where Oregon didn't bring 5 every down, so it made the dig/shallow read pretty easy (either the WLB/MLB was widening for the swing or were both dropping to hook) .

What should be interesting for COACHES is not what they are doing but how they are processing the information on the field. Just by segmenting the defense, picking on one particular defender they can make some pretty safe assumptions on where everyone else will fit and who becomes the best ball carrier in that situation.

I think what we have to remember is that all spread offensive systems strive in some way or another to displace defenders and in the process place an inordinate amount of structural stress on the defense's force or alley players. Whether it's RichRod's spread option or Noel Mazzone's version, both offenses are really trying to hammer on a defenses adjuster backer, which in most 2 hi looks is going to be the sam, at least most of the time. RichRod does it with the Zone Read and Zone Bubble, as we've seen in the excellent talks that Brophy has posted on the blog. For Rich, it's really about trying to make sure that the adjuster never gets into the box, he's the guy they need to control. Mazzone too wishes to attack the adjuster, but his objectives are little different; yes, he wants to run inside zone, but, as Brophy noted, it's really more about identifying the defense's anchor player in order to diagnose not the scheme in general, but more importantly, the defense's individual matches, which, if you think about it, in the era of match-zone is more important than ever.

In a sense, it shows how motion is being used again not so much as a way of gaining mismatches and what not, the offense's general scheme already takes care of that, but of diagnosing what it is that the defense is doing. So, in a way, it just shows how we are coming full circle with the spread. Motion that was once jettisoned is now coming back as a tool for identifying a defenses seams and stress points.

Also, as was noted above, motion is not used blindly by Mazzone. In the Missouri game they hardly used motion because MU is fairly straightforward structurally; with Oregon, however, it was necessary.

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

WHY NOEL MAZZONE: DENNIS ERICKSON AND THE ONE-BACK SPREAD OFFENSE

Over the course of this summer, Brophy and I have talked a lot of offense. As many of you know, we’ve focused much of our discussion on what Noel Mazzone is doing at Arizona State. And given the richness of this topic, I suspect that we will continue to do so throughout much of this college football season.

For me, perhaps the greatest upshot of these discussions has been the way it took me back in time to when I first got into coaching football. Specifically, it got me thinking about Dennis Erickson and how much I enjoyed watching his offenses at Wyoming, WAZZU, and Miami, which in turn got me to think more critically about his hiring of Noel Mazzone. Sure, Mazzone was one of his guys for a short while at Oregon State, but when Erickson was forced to replace Rich Olsen, he clearly had the pick of the litter. I mean, besides knowing Mazzone, which obviously counts for something, there had to other reasons why he chose him, rather than, let’s say, Dana Holgorsen, or some other hip, en vogue spread offense guru.

I think to get at this problem the right way we have to settle a few things about why Erickson found himself in such a situation in the first place. If we were to blindly swill the pap that ESPN spews, the reason was quite simple: Erickson’s job was on the line and Rich Olsen’s offense was too antiquated for today’s game. Now, I think most readers know where I stand on this matter, but for the sake of posterity, let’s understand that Rich Olson is an outstanding football coach and that the offense he coordinated was not outdated by any stretch of the imagination. The simple fact is that the administration forced Erickson’s hand, so a change had to be made. But this should not be interpreted as the administration taking the keys away from Erickson, because his choice of Mazzone reflects the degree to which, at a deep structural level, Noel’s offensive thinking is predicated upon the same set of fundamental beliefs and values as Erickson’s.

The reason I harp on this is because, and I mean no disrespect here, Mazzone’s incarnation of the spread is so medieval that it’s progressive. By this, I mean that the fundamental principles and structures upon which Mazzone’s offense is predicated are virtually identical to those upon which Erickson based his offenses throughout the 80s and 90s, which is to say – verticals, quicks, and zone running made easy by defensive displacement.

I don’t want to spend too much time on Erickson’s original offense. For those interested, please see Chris Brown’s treatment at Smart Football. The other source to consider is UTEP football, because for all intents and purposes the offense Mike Price runs today is not too terribly different from the one he ran back in the 90s at WAZZU.

With that disclaimer of sorts, I will say a word or two about the spread offense Erickson ran with great success from Idaho and Wyoming to Miami, Oregon State, and, at least initially, Arizona State. For those expecting gaudy route structures, Erickson’s may appear, at least upon first blush, somewhat basic; Erickson really did not rely much on layered concepts, such as Shallow, Drive, Mesh, etc, preferring instead to rely on vertical stem packages in both his quick and drop back games. The reason for this is very simple: Erickson never wanted to stop running the ball; he simply wanted to create defensive structures that would enable him to run the ball effectively inside. This is why Erickson from the very beginning emphasized stretching the defense from sideline to sideline, not only with formations, but concepts as well. Formations and splits that would effectively center the defense by inviting it to align players closely to the LOS were jettisoned in favor of five very basic environments that by alignment would engender some type of a Nickel response.

Diagram I. Tight End / Slot

Diagram II. Trips Closed (TE to the boundary)

Diagram III. Trey

Diagram IV. 3X2 (with Y or T Flexed or in the Slot)

Diagram V. 3X2 (with Y in the Formation)

And because Erickson never wanted to bring the defense towards the ball, his passing game, by design, was designed to create an environment that would stretch the field horizontally, which he would then attack vertically. Consequently, Erickson eschewed routes that could possibly negate the horizontal stretch of his formations, for those that would always “push” the defense off the ball, creating even more vertical space between it and the offense.

Does this mean that Erickson’s one-back was not a ball-control offense, that it was always trying to go for the deep shot? No, only that he sought a way of throwing the ball that would not draw the defense towards the formation, and thus, towards the ball. As a result, what you see is a pass offense based around vertical stems, be they seams and benders, or option routes paired with posts and digs over top.

For me, perhaps the greatest upshot of these discussions has been the way it took me back in time to when I first got into coaching football. Specifically, it got me thinking about Dennis Erickson and how much I enjoyed watching his offenses at Wyoming, WAZZU, and Miami, which in turn got me to think more critically about his hiring of Noel Mazzone. Sure, Mazzone was one of his guys for a short while at Oregon State, but when Erickson was forced to replace Rich Olsen, he clearly had the pick of the litter. I mean, besides knowing Mazzone, which obviously counts for something, there had to other reasons why he chose him, rather than, let’s say, Dana Holgorsen, or some other hip, en vogue spread offense guru.

I think to get at this problem the right way we have to settle a few things about why Erickson found himself in such a situation in the first place. If we were to blindly swill the pap that ESPN spews, the reason was quite simple: Erickson’s job was on the line and Rich Olsen’s offense was too antiquated for today’s game. Now, I think most readers know where I stand on this matter, but for the sake of posterity, let’s understand that Rich Olson is an outstanding football coach and that the offense he coordinated was not outdated by any stretch of the imagination. The simple fact is that the administration forced Erickson’s hand, so a change had to be made. But this should not be interpreted as the administration taking the keys away from Erickson, because his choice of Mazzone reflects the degree to which, at a deep structural level, Noel’s offensive thinking is predicated upon the same set of fundamental beliefs and values as Erickson’s.

The reason I harp on this is because, and I mean no disrespect here, Mazzone’s incarnation of the spread is so medieval that it’s progressive. By this, I mean that the fundamental principles and structures upon which Mazzone’s offense is predicated are virtually identical to those upon which Erickson based his offenses throughout the 80s and 90s, which is to say – verticals, quicks, and zone running made easy by defensive displacement.

I don’t want to spend too much time on Erickson’s original offense. For those interested, please see Chris Brown’s treatment at Smart Football. The other source to consider is UTEP football, because for all intents and purposes the offense Mike Price runs today is not too terribly different from the one he ran back in the 90s at WAZZU.

With that disclaimer of sorts, I will say a word or two about the spread offense Erickson ran with great success from Idaho and Wyoming to Miami, Oregon State, and, at least initially, Arizona State. For those expecting gaudy route structures, Erickson’s may appear, at least upon first blush, somewhat basic; Erickson really did not rely much on layered concepts, such as Shallow, Drive, Mesh, etc, preferring instead to rely on vertical stem packages in both his quick and drop back games. The reason for this is very simple: Erickson never wanted to stop running the ball; he simply wanted to create defensive structures that would enable him to run the ball effectively inside. This is why Erickson from the very beginning emphasized stretching the defense from sideline to sideline, not only with formations, but concepts as well. Formations and splits that would effectively center the defense by inviting it to align players closely to the LOS were jettisoned in favor of five very basic environments that by alignment would engender some type of a Nickel response.

Diagram II. Trips Closed (TE to the boundary)

Diagram III. Trey

Diagram IV. 3X2 (with Y or T Flexed or in the Slot)

Diagram V. 3X2 (with Y in the Formation)

And because Erickson never wanted to bring the defense towards the ball, his passing game, by design, was designed to create an environment that would stretch the field horizontally, which he would then attack vertically. Consequently, Erickson eschewed routes that could possibly negate the horizontal stretch of his formations, for those that would always “push” the defense off the ball, creating even more vertical space between it and the offense.

Does this mean that Erickson’s one-back was not a ball-control offense, that it was always trying to go for the deep shot? No, only that he sought a way of throwing the ball that would not draw the defense towards the formation, and thus, towards the ball. As a result, what you see is a pass offense based around vertical stems, be they seams and benders, or option routes paired with posts and digs over top.

Now, before continuing, I want to head a potential problem off at the pass: rightfully, many coaches would look at this and say that without an aggressive shallow or drive game, how did he manage to control the linebackers? After all, this is essentially the problem Northwestern had a decade ago after their first big year in the spread offense; they had a half-field passing game to either side of the formation, but with nothing over the middle because of wide splits their receivers took. For this, much more so than Northwestern, Erickson used option routes that effectively prevented the linebackers from providing hard and aggressive run support.

So what does any of this have to do with Noel Mazzone? I think what we need to remember is that for a while, and even recently, when coaches hear Mazzone’s name they equate it not just with Snag, but with shallows and other layered concepts. And there is undoubtedly a great deal of truth to this, because for a while shallows and crossers were the bread and butter staples of any Mazzone offense; and while he recognized the need to get vertical even then to prevent people from squatting on his underneath stuff, it was, as will be covered in a future post, usually paired on the back side of his shallows. But shallows are not what characterize Arizona State’s current offense; in fact, one can say that while shallows and drives remain an important part of Mazzone’s current offense, they now play a decidedly more secondary role to his Arizona State’s Vertical game. And this is why, I think, Mazzone was so attractive to Erickson, because Mazzone’s current offensive thinking, from the role formations and verticals, to a simple, yet effective inside zone running game, effectively is entirely in synch with Erickson’s base offensive values.

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Attack Nodes: Running From The Gun

This entry (and most that proceeded and will follow) is a result of a summer-long Noel Mazzone discussion between hemlock and I. Mazzone represents the offensive innovation of the 90s maturing and adapting to the constantly changing world of football. If you’re over 30, you may be able to appreciate how an imaginative spark can ripple into a wave of change as time passes, sometimes taking decades to blossom. Specifically, how the things done in the late 80’s ended up shaping the zeitgeist of football we know today.

The previous posts featuring the Alex Gibbs staff clinic was simply a prelude to the larger focus here. The stretch clinic illustrated the brainstorming involved as offenses adapt to living in the gun full-time (“we’re not in Kansas anymore”).

As those videos documented, there came a time when Gibbs just threw out tight zone because it wasn't worth investing in as he was getting a favorable return with stretch. While zone and stretch share similarities, many offenses are finding it is easier to just drop one or the other because they just don't have enough time to become proficient in the necessary skills to run them both.

While I believe there are some distinct “families” emerging here, I don’t truly believe there is a right or wrong path (both have considerable merit). With that, I will preface this with the disclaimer that most run attacks aren’t as codified as they will be depicted here. In this post, I’ll attempt to illustrate what issues offenses face by choosing a particular path. This post won’t offer any absolutes or hidden truths, its just an editorial on where many offenses are headed.

INSIDE

Nearly two decades since Dennis Erickson made the above comments regarding his philosophy, that same tenet holds true for Mazzone. You spread the formation (horizontally) to run the ball. You aren’t running the ball to areas of the field where you are drawing defenders to (outside). With one-back, you empty the box to make running inside easier (by eliminating defenders by alignment) with the added dimension of utilizing outside receivers.

I believe the most interesting thing we can witness from the Arizona State Offense is how truly simple it is (we’ll get into greater detail later, but much can be seen by examining their protection). It is this simplicity that allows it to be so effective and helps package the entire offense into easily distilled decisions for the quarterback. Mazzone’s run game is an extension of galvanized concepts he has carried with him during his career.

What is distinct about Mazzone is how he’s held true to that Erickson philosophy. He doesn’t run stretch, he’ll run zone, zone read and trap, but for perimeter attacks, it is reduced to flash, tunnel, slow screens, and swing from play-action. This isn’t unlike West Virginia under Rich Rodriguez or Tulsa under Herb Hand and Gus Malzahn, who were renowned for speed sweeps and power, but made their living off of zone and zone-read options.

For a 4-wide gun offense, zone can serve as the sprint-draw of the 2-back offense; an effective way to gain a numeric advantage against a defense with minimal defenders in the box. Zone, by itself, would allow the offense to get 5 linemen on 5 defenders and insure at least 1 double-team at the point-of-attack. With the way Mazzone packages his offense, the run game is actually able to further weaken the integrity of the defensive front by systematically isolating backside defenders with a horizontal stretch (making the play-side C-G-T the only crucial blocks needed). With zone-read, the tight zone action can be used to:

For a 4-wide gun offense, zone can serve as the sprint-draw of the 2-back offense; an effective way to gain a numeric advantage against a defense with minimal defenders in the box. Zone, by itself, would allow the offense to get 5 linemen on 5 defenders and insure at least 1 double-team at the point-of-attack. With the way Mazzone packages his offense, the run game is actually able to further weaken the integrity of the defensive front by systematically isolating backside defenders with a horizontal stretch (making the play-side C-G-T the only crucial blocks needed). With zone-read, the tight zone action can be used to:

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDE  The other end of the spectrum here is where most other teams are at in terms of the spread run game, using stretch as the primary means of running the ball. This creates a bit of a quandary that opens a door of additional answers.

The other end of the spectrum here is where most other teams are at in terms of the spread run game, using stretch as the primary means of running the ball. This creates a bit of a quandary that opens a door of additional answers.

When you operate in a true one-back gun environment without a tight end, running stretch can be a challenge. Without a tight end, you need the play-side tackle to reach an athletic defensive end who is in pass-rush mode for the better part of the game.

If you’re aiming point is to a ghost tight end, the read will most often be closed or consistently muddy for the runner. With all linemen bucket-step reaching play-side, it really amounts to just cutting off/getting in the way of defenders. Because that second down defender probably won’t get reached, he will impede the runner from actually bouncing outside (with second-level defenders gap filling inside of him), leaving the cut back the only option.  To make up for this liability, you can attempt to fortify your read by adding another blocker (back or tight end) and simply try to invest more resources to improving the run (read). This now invites more defenders back into the box which works contrary to the reason most spread offenses “spread”.

To make up for this liability, you can attempt to fortify your read by adding another blocker (back or tight end) and simply try to invest more resources to improving the run (read). This now invites more defenders back into the box which works contrary to the reason most spread offenses “spread”.

As an illustration, we’ll use Tony Franklin as the contrast to Mazzone’s run game, though there are many who share the same philosophy of Franklin. Another “coach’s coach”, Franklin has evolved his offense tremendously over the past decade and has been forced to find answers with limited talent. The current version of his offense is largely owed to Dwight Dasher during his time at Middle Tennessee, where there was a heavy reliance on stretch and dash. While at Louisiana Tech, Franklin began tapping into these skill sets more due to the reliance on running back, Lennon Creer (considerably more two-back, “wild dog”, truck, and power). 2011 will likely feature more of the same with the addition of a more mobile passer in Colby Cameron (update: it appears 17-year old Nick Isham is now the starter).

These ‘variations on a theme’ may be required to survive if stretch is going to be the source of your gun run game. While all of these counters off of stretch action open up avenues of stress for a defense (it provides a prescription for every symptom), they also require your offense to carry more tools into a game (more plays). We’ve gone over several of these adaptations before and we don’t intend on covering old ground in this post. The point is to illustrate that current meme of stretch offenses centers around heavily exploiting backside horizontal voids, call it your “stretch counter”, if you will.

This all just accentuates the recurring theme that as things evolve and adapt, it all is cyclical. Trends and flavors of strategy have to remain organic and willing to adapt to their environment to survive.

There isn't any assertion here on which method is the best. I am attempting to highlight the efficiency of one method over another. Both offensive styles will run nearly the same passing concepts, both 5-step, quick, and screens. The question would be posed on how much of a return should you expect on what is needed to be invested to make your run game from the gun work ( when operating from a true 4-wide, sans tight end, environment )? To base your run game out of stretch when you don't use a tight end can become expensive, because it will necessitate the offense to incorporate the many variations to keep it viable.

** Hemlock has followed this with additional perspectives on Noel Mazzone and how a few concepts have evolved through the last decade and how Mazzone marries it altogether.

The previous posts featuring the Alex Gibbs staff clinic was simply a prelude to the larger focus here. The stretch clinic illustrated the brainstorming involved as offenses adapt to living in the gun full-time (“we’re not in Kansas anymore”).

As those videos documented, there came a time when Gibbs just threw out tight zone because it wasn't worth investing in as he was getting a favorable return with stretch. While zone and stretch share similarities, many offenses are finding it is easier to just drop one or the other because they just don't have enough time to become proficient in the necessary skills to run them both.

While I believe there are some distinct “families” emerging here, I don’t truly believe there is a right or wrong path (both have considerable merit). With that, I will preface this with the disclaimer that most run attacks aren’t as codified as they will be depicted here. In this post, I’ll attempt to illustrate what issues offenses face by choosing a particular path. This post won’t offer any absolutes or hidden truths, its just an editorial on where many offenses are headed.

INSIDE

I believe the most interesting thing we can witness from the Arizona State Offense is how truly simple it is (we’ll get into greater detail later, but much can be seen by examining their protection). It is this simplicity that allows it to be so effective and helps package the entire offense into easily distilled decisions for the quarterback. Mazzone’s run game is an extension of galvanized concepts he has carried with him during his career.

What is distinct about Mazzone is how he’s held true to that Erickson philosophy. He doesn’t run stretch, he’ll run zone, zone read and trap, but for perimeter attacks, it is reduced to flash, tunnel, slow screens, and swing from play-action. This isn’t unlike West Virginia under Rich Rodriguez or Tulsa under Herb Hand and Gus Malzahn, who were renowned for speed sweeps and power, but made their living off of zone and zone-read options.

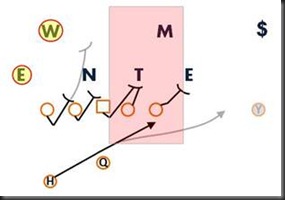

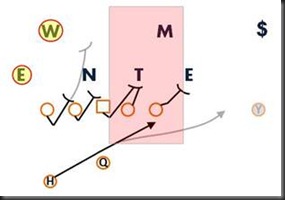

- manipulate the backside defensive end into caving down inside and open up the quarterback keep (zone-read)

- keep the WILB flat-footed and out of position to defend the backside snag or F quick (flare)

- hold the play-side safety longer to provide an extremely clear read to run verticals against

The other end of the spectrum here is where most other teams are at in terms of the spread run game, using stretch as the primary means of running the ball. This creates a bit of a quandary that opens a door of additional answers.

The other end of the spectrum here is where most other teams are at in terms of the spread run game, using stretch as the primary means of running the ball. This creates a bit of a quandary that opens a door of additional answers.

With a tight end

Without a tight end

You are also aiming for an area where you’ve already drawn defenders to by alignment (perimeter). This can be a cheap way of gaining yards (relying on cutting and reaching on the line), much like flash screens, where you don’t need killer blocks to gain positive yards. You don’t have to be tremendously athletic to reach a defender, but the better the athlete, the better the backside runs will be (because your backside guard/tackle can actually get close enough to cut backside linebackers).  To make up for this liability, you can attempt to fortify your read by adding another blocker (back or tight end) and simply try to invest more resources to improving the run (read). This now invites more defenders back into the box which works contrary to the reason most spread offenses “spread”.

To make up for this liability, you can attempt to fortify your read by adding another blocker (back or tight end) and simply try to invest more resources to improving the run (read). This now invites more defenders back into the box which works contrary to the reason most spread offenses “spread”.

Add a back to insure your chances at the point of attack

The other alternative to making stretch work is to rely on the one guy your “spread” offense is centered around, the quarterback, to assume a dual-role as a runner.

Make your quarterback a runner (BOSS)

This limited end-game is what leads most gun offenses to two answers. - Use the bucket-step skill set of stretch and add to it by skip-pulling backside linemen for power (adding blockers to the POA)

- Purposely use stretch action to attack inside voids created by pursuit

now the horizontal stretch on the backside linebacker becomes more pronounced.

truck

Crunch

Stretch read (Flame/Fire)

Dash

You may need to invest more resources in your run game, but the potential for a greater dividend is there. That being said, throwing a flash screen off your inside zone run action is one thing, it can become an even more explosive off of stretch action (see below) because of how it creates an inside void for the receiver to run through. This all just accentuates the recurring theme that as things evolve and adapt, it all is cyclical. Trends and flavors of strategy have to remain organic and willing to adapt to their environment to survive.

There isn't any assertion here on which method is the best. I am attempting to highlight the efficiency of one method over another. Both offensive styles will run nearly the same passing concepts, both 5-step, quick, and screens. The question would be posed on how much of a return should you expect on what is needed to be invested to make your run game from the gun work ( when operating from a true 4-wide, sans tight end, environment )? To base your run game out of stretch when you don't use a tight end can become expensive, because it will necessitate the offense to incorporate the many variations to keep it viable.

** Hemlock has followed this with additional perspectives on Noel Mazzone and how a few concepts have evolved through the last decade and how Mazzone marries it altogether.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

BACK TO THE FUTURE: SLIDING WITH NOEL MAZZONE

Last season, Arizona State was, at least in terms of wins and losses, a very average team. After all, ASU won on six games, two of which against FCS teams. But for anybody who watched ASU play last year, it was clear that they were, perhaps, the best 6-6 team in the land. I saw them play live at Camp Randall against the Badgers and remember walking away from the game with two thoughts: 1) This team will get better as the year goes on and they will peak in November; 2) Their offense is really neat and will undoubtedly be the subject of much scrutiny in the offseason, assuming, of course, that they get it down.

Undoubtedly, ASU improved, and without question, it was due primarily to the great strides they made mastering Noel Mazzone’s new offensive scheme. In the ensuing series of posts leading up the start of the new season I will discuss in some depth the nuances of ASU’s offense. While one of my aims is clearly to shed some light on what I believe are exciting advances in the passing game, another one of my goals is to discuss the offensive thought of one of the game’s most innovative, but frequently overlooked, offensive thinkers, a coach, who, if things bounce the way they should this year, could very well end up the next HC of the University of New Mexico – Noel Mazzone. So while I will definitely talk about what Coach Mazzone is doing at ASU now, I will also provide a detailed sketch of the evolution of his offensive thought over the years, from his years at TCU of the old Southwest Conference to the Jets of the NFL.

First, I think it would be helpful to provide a little immediate background to his current position. Dennis Erickson hired Noel Mazzone after the conclusion of the 2009 season. He replaced Erickson’s longtime friend, Rich Olson. Erickson’s decision to hire Mazzone represented a change in his offensive thinking, for while Erickson has always been a spread one-back coach, he was always more of a vertical stem, option route guy who, by and large, never invested much in the type of layered, over-under schemes for which Mazzone made his reputation.

Why Mazzone?

I guess the first question that needs to be asked is: What is so special about Mazzone’s offense that it merits such close scrutiny. I mean, sure, it was extremely effective last year, put up tons a points, even more yardage, and was, overall, very exciting, but isn’t it just another spread offense? Undoubtedly, all of this is true, but there are some differences in Mazzone’s approach that are clearly worth studying, not because they are necessarily better than those practiced by other coaches, such as Mike Leach, Tony Franklin, or June Jones, to name only three, but because it shows how spread football is progressing by returning to its origins.

Protection:

In general, most pass-heavy spread offenses employ man protection schemes. This is not something unique only to Air Raid teams, but the vast majority of single / empty spread offenses. There are many reasons for this, but one of the main reasons, I believe, is that the rise of single and empty environments coincided with that of the fire zone. To appreciate this we need to have a little history in regards the development of slide protection. Generally speaking, sliding as a means of protecting the quarterback came into vogue during the early 1980s as a way of dealing with inside and outside pressure to the quarterback’s blindside with a single move. In a sense, sliding away from the call was a way of narrowing the quarterback’s field of vision, making it so that he would not have to worry about unexpected pressure by an inside backer through the “B” gap or number 4 flying off the edge.

By and large, sliding was how most one-back teams protected during this period. But there have always been some issues related to stunts and games along the front that posed some real problems for slide teams. In particular, any type of stunt that crosses the face of the center, regardless of direction, threatens the integrity of the protection, in part, because of the kick-slide technique upon which the protection is predicated. (Matt, I’m thinking here of dogs, but of specific stunts, like the “t-chain” in which the 3 and the 4I or 5 slant the A and B gaps respectively with the shade ripping off their backsides into the opposite C) This type of movement exposes the twin problems of “depth” and “center” of the scheme; for unlike vertical set man teams, and I’m not just talking here about Air Raid programs, units that slide gain very little depth and separation from the defensive front after the snap. Consequently, any quick horizontal movement across the line’s fulcrum, the center, takes advantage of center’s compromised base, that is, the side to which he steps in order to combo on the shade with the adjacent guard or post on the one technique while keeping an eye on the stacked backer. While on paper that step may seem inconsequential, it places the center in a compromised position from which it is difficult to play catch up with any type of hard crossing action. For this reason, many one-back teams began to rely more on vertical set man schemes that enables the line to gain depth in order to “sort” and dissect the pressure as it comes.

Without question, I think we can see why coaches, especially in recent years, chose to pursue man schemes, that while requiring more tweaking on a week to week basis, nevertheless, at least until recently, offered more tactical leeway for the players themselves, as well as more strategic flexibility for the coaches in terms of maximizing the number of people they could release on any given play. I bring this up because with the advent and development of fire zone packages, sliding became increasingly costly in the sense that in order to protect the QB teams were forced to limit the number of receivers they could release on a given route, which, if we pause to think for a second, simply plays into strengths of any fire zone coverage by eliminating the very receivers for which any five man pressure scheme fails to account.

And this is what makes what Noel Mazzone is doing so interesting, because unlike everybody else, ASU is very much a slide team, and one, mind you, that has hardly any issues with protection. Now, before getting into the nitty-gritty of his protections packages, let’s briefly consider why Mazzone chooses to slide. Mazzone’s reasons for sliding are simple and can be traced back to his days at Auburn. In a word, Mazzone wants the QB to focus on one thing and one thing only: THROWING TO VOIDS. That is to say, Mazzone does not want, in no uncertain terms, for the QB to be concerned with what the defense is doing; the QB’s sole job is to focus on delivering the ball. And what’s interesting about this is that because his goal to get five players out as much as possible, Mazzone, in a sense, seems to want to make it schematically impossible for the QB to bring another blocker back into the formation, and his way of doing so is to make the QB feel protected by securing the side of the field to where there is no grass.

I know that the above statement seems somewhat strange, but it really is keeping completely with the old Hal Mumme maxim of throwing the ball to the grass. But in order to appreciate this point and its import to how Mazzone slides today, let’s say a word or two about basic slide protection.

Below is basic slide protection, or what ASU today calls “ACT,” versus what I like to call “country stack,” or your garden variety 42 or 44 look.

So, working from right to left, this is what we have:

RT: Man on

RG: Man on

C: Linda call to the Mike stacked over the shade; post on the shade with the guard

LG: Set with the Center on the shade

LG: Man outside; key Will backer for possible Joker call.

RB: Key Sam to Adjuster/Strong Safety; responsible for most inside threat.

QB: Throw the Void (this is not Hot; more on this in future posts)

Now, I think the fundamentals of this protection are all fairly self evident. If the tackle senses that number four is going to come, he will make a Joker call, which will, depending on whether it’s an even or odd front, trigger either a three or four man slide to that side beginning with the first uncovered lineman.

Generally speaking, this scheme is fairly stable in that the line slides opposite the back in order to secure the QB’s backside thus making the side to which the back is checked to the call side, regardless of how many receivers are deployed there.

But what happens if the scheme, regardless of whether there is a back behind the line or not, is essentially an empty one with no check release? For all intent purposes, this nothing really changes for the line, with the exception that now the front side tackle has what amounts to a duel read in that he must eye the Sam backer and be ready to pick up the nearest inside threat, thus making the adjuster backer the sole responsibility of the QB.

As noted earlier, one of the strengths of this approach is its stability, the fact that the QB know from the very beginning that his backside is, at least in principle, secure, thus placing everything else firmly within his immediate line of vision. But this has also been one of the scheme’s greatest drawbacks, especially in the wake of the fire zone craze, because DC’s could always set their fronts, stunts, games, and fire packages to the back’s call, making moot, in effect, the very purpose of the slide itself.

Herein lies the beauty of Mazzone’s innovation, one that I believe, at some level or another, reflects the influence of the Hal Mumme, Mike Leach, and other Air Raid coaches: rather than simply slide away from the back, Mazzone freed his line to slide to where the defense was on the field, which is another way of saying, away from the grass and towards where the defense had the potential to deploy the most people.

On the surface this sounds odd, but it really makes quite a bit of sense, because across the football field there are really only three generic types of zone pressure: boundary, middle, field. Moreover, most teams, as well as conferences, for that matter, especially at the college level, usually have signature pressure packages and preferences. For example, both the Pac 12 and Big 12 are heavy field pressure conferences. Despite the fact that boundary pressure is easier to disguise, most programs in these conferences prefer to fire it up from the field, so this is where their defensive numbers are going to be. Below are two diagrams, the first offering a global perspective, the second illustrating how ASU slides to the numbers.

This is your standard field blitz from a three man front. There are different ways to package this concept, but the nuts and bolts of it are pretty simple. For the same reasons, it should be easy to see where the defense is putting its numbers. If we count the nose, we get six players to the field, leaving only five to the boundary. Yet if we were to employ a standard slide here away from the back, it immediately becomes evident that we would, in effect, be protecting away from the threat. But as the diagram below illustrates, ASU’s answer enables them to account for this with no difficulty.

So, rather than have his line slide into the boundary away from the pressure, Mazzone has his guys slide into it with a four man slide that not only seals off the interior paths of pursuit to the quarterback, but the edge as well, leaving the boundary tackle to ride the end out with the back checking inside out from Mike to Sam.

The one question that remains, however, is whether or not the frontside is now where the back ends up or his original position? Simply put, the frontside remains the side of the back’s original alignment. Now, I recognize that some may say, and rightfully so, that doesn’t this defeat the purpose of slide protection; after all, the reason coaches slide is to secure the backside, right? My answer to this is that that the secure side needs to be the side from wherever the pressure is coming from; it is senseless to protect the QB’s backside if there’s more grass there than there are jerseys with numbers on them.

Concluding Remarks:

In closing, I think it’s necessary to note that a vertical set man scheme is just as up to the task as sliding. Why, then, does Mazzone slide? In addition to the reasons outlined at the beginning of this piece, we should consider the place of the drop-back game within the whole of his offense. One reason Mazzone continues to slide is because of the extent to which his quick, screen, and zone games are integrated into a near seamless whole with his dropback package. In essence, Mazzone views these not as separate aspects of the offense, but as protective extensions of his core passing game. And by “protective” I mean that they tie so well into his slide protection scheme not only tactically, that is, how they appear to the defense, but also, and perhaps more importantly, pedagogically for his offense’s players. So, from a global perspective, provides Mazzone with a flexible way of protecting the QB that also enables the other central components of his relatively simple, if not reductionist, yet incredibly dynamic offensive system.

>>> MORE FROM HEMLOCK <<<<

Friday, July 1, 2011

Food for thought….

Just passing some things I found to particularly interesting as we wind up towards another season….

Noel Mazzone 1-Back Offensive System

Using the Tony Franklin model of marketing and production, it looks like the charismatic, innovative, and altogether-likeable coach’s coach, Noel Mazzone, has his trademarked football system available through Championship Systems. Though I know little about this new product, I'm sure this will be a great resource for coaches, the same as “The System” has been for so many others.

If you've seen any of Mazzone's presentations this year or caught any of his webinars with Glazier, you'll know he's pretty liberal with the game and (recent) practice footage and explaining in detail each concept he uses and how he applies it in a game.

Visit their website ( http://nzonesystem.com/ ) or give them a call at 719-964-2111 for more information.

* if we’re lucky, hemlock will return soon with a deep look at Mazzone’s philosophy over the years, trending the prevailing memes of the game from the past two decades.

Paul Alexander’s Peak Performance

For those with a sense for deeper reflection and cognitive understanding, Oline guru, Paul Alexander is self-publishing a work that shows considerable promise helping coaches become more efficient skill teachers.

This should provide a real interesting and dispassionate perspective about coaching and training their students for unleashing consistent excellence.

http://www.perform-coach.com/

Noel Mazzone 1-Back Offensive System

why the hell not?

Using the Tony Franklin model of marketing and production, it looks like the charismatic, innovative, and altogether-likeable coach’s coach, Noel Mazzone, has his trademarked football system available through Championship Systems. Though I know little about this new product, I'm sure this will be a great resource for coaches, the same as “The System” has been for so many others.

If you've seen any of Mazzone's presentations this year or caught any of his webinars with Glazier, you'll know he's pretty liberal with the game and (recent) practice footage and explaining in detail each concept he uses and how he applies it in a game.

We currently have all the drill and play clips from Coach Noel Mazzone’s ASU spring practices and hundreds more offense clips for client coaches to study. He has already completed his spring install schedule with ppts and play rules, his HS playbook, and video cuts of QB drills. We also have his 48 page QB manual and 40 page QB techniques/fundamentals book for the development of young QBs for coaches to print and have.

We have just put up his OL techniques, vertical set, and pass protections webinars and his whiteboard series filmed at ASU has been a huge hit with clients! He begins his summer webinar series this Thursday for all his members only coaches and will be covering his entire offense from A-Z with drills, video, play cut-ups, and coaching strategies. His HS playbook, install packets, and QB drills/video are excellent! Plus, he just finished a one on one session with one of our client college staffs in Minneapolis and a team camp for a high school in Idaho!! Everywhere he goes, he gets rave reviews on what he is doing with his system!

Visit their website ( http://nzonesystem.com/ ) or give them a call at 719-964-2111 for more information.

* if we’re lucky, hemlock will return soon with a deep look at Mazzone’s philosophy over the years, trending the prevailing memes of the game from the past two decades.

Paul Alexander’s Peak Performance

For those with a sense for deeper reflection and cognitive understanding, Oline guru, Paul Alexander is self-publishing a work that shows considerable promise helping coaches become more efficient skill teachers.

This should provide a real interesting and dispassionate perspective about coaching and training their students for unleashing consistent excellence.

http://www.perform-coach.com/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)