Talking ball with Harbaugh as he shares his secrets to creating a better passer...

Thursday, December 29, 2011

Monday, December 26, 2011

Football’s Illusions

We want diversity, but we don't want it to be an argument. But that's what diversity is.

Sometimes the arguments are creative. When you start a dialectic between people who are different, it benefits... I believe in arguing.

I'm often accused of being opinionated and argumentative, I plead guilty to that, but I've never had anything not end up better because people in the same room were arguing back.

-David Simon

-David Simon

This post is an attempt to articulate a deeper response to understanding today’s game of professional football and the culture that surrounds it. Please understand that there are various nuances to consider and this is not intended to be the cynical fire-starting rant that it may appear to be at first glance.

Hemlock and I are presenting our views on this subject for posterity and reflection on the impact of mass media in shaping the game of football in the current age. In a recent discussion at Coach Huey.com, the issue of NFL scheme variety was presented. Is there really a difference between one team from another, when they all essentially are running the same thing? And if they are the same, why are we being constantly told about / sold on the facets that are unique to such-and-such scheme?

Monday, December 19, 2011

Sean Payton: Quarterbacking

Here is a decent resource for getting a young quarterback grounded in some solid fundamentals on throwing mechanics (circa 1992). Now, granted there are a few things in the video that don’t lead to efficiency, but, hey…..this was over 20 years ago. You’ll see a young assistant coach named Sean Payton running quarterback footwork and throwing drills.

If you want a great indoctrination of flawless throwing, you’d better invest in Darin Slack C4 and R4 materials.

Darin Slack Quarterback Training

Saturday, December 10, 2011

ROD DOBBS: Teaching & Installing Zone Runs

Right behind the Alex Gibbs staff clinic with the UF staff, this has got to be one of the most comprehensive instructions on zone running. Rod Dobbs, a Gibbs disciple, who is now coaching at Chaparral High School in Denver, CO, clinics a high school staff while he was running the offense for Northern Colorado. Dobbs goes over the entire scheme, technique, and how to make it work during a season in this 6 hour presentation.

This off-season, why not establish some relationships with other coaches and invite them in to get your staff on the same page for next year.

This off-season, why not establish some relationships with other coaches and invite them in to get your staff on the same page for next year.

Sunday, December 4, 2011

NC: Rematch Bama vs LSU

Well, its set.....the SEC rematch between #1 LSU and #2 Alabama. While it may not be technically "fair" from an LSU perspective to have to face off against a team it already defeated on the road in regular season, I feel from a football perspective, these truly are the two best teams in the country.

As a fan of matchups, I really didn't want to see LSU play Oklahoma State (though it would be entertaining), as I don't feel the Cowboys really had enough dimension to take on this LSU team. We've included a concise recap of the first meeting this season below (more analysis likely to come). For what its worth, it should be noted that the majority of LSU's starters (with the exception of QB & 2 LBs) are all underclassmen, so barring a lot of early declarations for the NFL draft, you have a team poised for a run in 2012, too. Alabama, too, starts a good majority of underclassmen (meaning, this is really about recruiting supremacy more than schemes and strategy).

Poetically enough (for this blog), TCU squares off against Louisiana Tech in the Poinsettia Bowl, in what should be an exciting matchup. On a personal note, I'll likely be treated to the surprise switch of teams for the Jewella Slumdog, otherwise known as the Independence Bowl, featuring Mizzou and John Shoop's North Carolina Tarheels.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

THE EDGES OF CONCISION

A couple of weeks back, just before the holiday, I was in Washington DC for another profoundly boring, tedious, and ultimately, pretentious academic conference. After giving my talk and fielding an hour or so of numbing questions I went to the hotel lounge to unwind with the help of my two best friends, Mr. Jameson and Mr. Glenfiddich. I was lucky that night because I managed to grab the TV before the fireplace and monopolize it – a good move indeed because the boors who eventually descended like locusts would undoubtedly not have wanted to watch something as stimulating as the game between Iowa State and Oklahoma State that fine evening. Now, no doubt because of the good company of my two aforementioned friends, I was just a bit distracted and unable to fully digest and appreciate what was unfolding in Ames that night, but I knew I had found something quite appealing to my oh so prosaic senses, especially when the Cyclones had the ball.

I got back the next day to Madison in time to watch another interesting match – that between Baylor and Oklahoma. And this is when, with the help this time of two other friends, Earl and Lady Grey, along with a healthy dose of lemon combined with a quick shot Ms. Brandy (muddled, of course), it all started to dawn on me, almost like the initial testament Joseph Smith experienced somewhere in New York state. It all began when one of the prophets, Matt Millen, declared in no uncertain terms that if Baylor wanted to be successful against OU that they needed to move RGIII around so as to change his launch points and prevent the Sooner D from teeing off on him. For a moment, I agreed with the prophet and considered myself, with bit of self-loathing, fortunate to be in a position to take in his divinatory powers. But then something happened: the game continued, Baylor continued, by and large, to keep RGIII in the same place, and eventually the Bears won.

That night I went back and watched the ISU-OSU tilt again and noticed the same thing; hardly any pocket movement. This jogged my memory a bit and sent me back to my Arizona State cutups, which brought my attention to something I had completely taken for granted at some level or another: none of these teams protect their QBs by changing their QBs’ launch points. Does that mean that they do not move the pocket? Of course not. Only that when they do so it’s primarily to isolate a single receiver on an easy throw, usually in a short yardage situation; in other words, when they move the QB it is not because they necessarily believe that it will help them protect him more effectively.

For anybody well-versed in the fundamentals of protection, this all seems counter-intuitive, right? I mean, after all, a stationary QB is a sitting duck just waiting to get blown apart by a defense that simply needs to stay in its lanes in order to bring their pressure home? How then do these teams do such a great job of protecting their QBs, especially when they are most of the time releasing not three, but four and five guys and are thus never protecting with any more than six people? If we pause to think about it for a second or two, the answer becomes self evident: all these teams secure their QBs by ensuring that the A and B gaps are always solid and by protecting their edges by way of their KEY screen games that come off of their inside zone schemes. Since Baylor, OSU, ISU, and ASU aggressively use their KEY games they are able to displace rushers and thus widen the edge thus increasing the distance a potential rusher must cover in order to get home. But this is only applicable if the defense continues to roll the dice, as it were, because the KEY game itself forces a defense to consider the potential costs and benefits of bringing such pressure.

This is yet another example of concision. By formulating and integrating packages so that they protect one another, not just the QB as a physical being, but concepts in and of themselves, they are able to reduce the number of things they need to carry in any given game. For all these teams, the KEY game along with whatever versions of ROSE and LINDA they run work to protect not only their respective 2 and 3 man SNAG games, but also their Shallow and Drive packages as well.

In a perverse sense then, protection is as much about the periphery as it is the center.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Offseason to dos

As offseason has fallen upon us, it’s that time of year to evaluate yourself and your philosophies. In my current situation, we have had 2 very poor seasons (2 wins in 2010, 3 wins this season) after being 25-3 the two previous seasons. Obviously, after those two ends of the spectrum it is hard to look at things thru the same eyes. We are a spread-to-run team. In 2008 we had a Jr. tailback and a Jr. QB. The QB missed half the season with a broken collar bone. The tailback carried the load and was not the same player in week 13 as he was in week 1. When the season was over, we had a very definite plan. It was to revamp our passing game to give us the opportunity to be balanced. We will always be run first but we knew that for an opportunity to advance further in the playoffs we were going to need to be more efficient throwing the ball. That was an easy offseason. We visited with the staff at the University of Texas for 3 days and incorporated 4 routes (3 quick game & 1 pap). We also did some addition by subtraction. We eliminated several routes and really narrowed our focus. Bottom line…we double our yardage, had more completions than attempts from the previous season, and doubled our TD’s, while keeping the same number of interceptions. That was a successful offseason.

Now, after two dismal seasons, where do you start? Do you being looking closely at personnel, practice plans, philosophy, staff changes, etc.? There was so much wrong where do you start making it right? I coach the wide receivers and here is what I decided to do as a start for me. Our previous head coach left a bunch of COACH OF THE YEAR MANUALS in the field house. I have seen them there for years and grabbed one or two for trips to the throne before but never really thought of using them as a learning tool. Just recently, I grabbed one from 1983 and I wanted to share with you some of the things that were in it that have got the mind firing and the x’s & o’s flowing again for me.

The first page had a tribute to Bear Bryant and his famous words –“Am I willing to endure the pain of this struggle for the comforts and the rewards and the glory that go with the accomplishments? OR : Shall I accept the uneasy and inadequate contentment that comes with mediocrity? Am I willing to pay the price of success?”

That was enough to get me going. The rest of these tidbits are just a few things I jotted down that I thought were relevant NOW just as they were in 1983. My top 10…

1. You have to know what you are doing and what you want to accomplish. Don’t do it just to be doing it.

2. Get excited about the 4 yard play.

3. DO YOUR BEST. I don’t want the KAMIKAZE pilot that flew 33 different missions.

4. Factor of 11 – There are 39,916,800 ways to line up 11 objects for all of you multiple guys.

5. Roger Bannister was the first to break the 4 minute mile. It was broken 43 times the next 4 years. Don’t put limitations on yourself.

6. Be intense enough to get the job done, but relaxed enough to enjoy it. (AMEN)

7. Again from 1983…Today a player will want to know why you want him to run thru a wall. You have to tell him why and then he will run thru it.

8. You have to be willing AND ready to throw on first down and from any place on the field.

9. Have people around you that like to work.

10. Be known for something. Be known for something you hang your hat on.

So what is your plan? What are you going to do? For those wanting to share ideas and throw things around….lets do it blog style, or shot me an email cmeans@denisonisd.net. As you may have seen in my other post, I am a HUDL guy that takes full advantage to the exchange features. If interested in swapping game films, cut ups, drills, etc… shot me an email.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Mazzone Revisited

I wasn’t quite sure if we captured the premise of the Iowa State lesson of schematic concision well enough in the last post. Admittedly, it was an off-the-cuff editorial to a climactic match. I also wasn’t sure if we have done a complete enough job to date on stressing the simplicity of concepts within an offense (hemlock has tackled this exceptionally well in previous posts), particularly as it relates to Noel Mazzone this fall. Yes, we get that Arizona State has underperformed this season and Erickson will likely be gone at the end of this year (though it is a shame, considering how explosive their offense has been), but I don’t believe that discounts the value of learning what is working with Mazzone.

With this in mind and to serve as a type of sidebar edification on the matter, we’re “reposting” an exchange offered by hemlock and I on COACHHUEY (explaining Mazzone’s system). So not to break the flow of dialogue (or require any actual work on my part) I’m leaving the posts as-is in the sequence they occured . Hemlock’s thoughtful prose and profound commentary is in gold, while my rambling gibberish is in diarrhea green.

** I realize some of the video (through Vimeo) hosted here is hard to come by. If you are not aware of how to rip flash already, I’ll direct you to use Firefox and download the video add-on. Start a video, then enable the download (and its yours).

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

It IS zone-read, but its all controlled/filtered through a systematic way of horizontally stretching the defense, while at the core being vertically orientated (zone-read, F swing, Stick/Snag/Scat/Drive/Shallows/Verts/and tons of screens). There is an efficiency in his application (which is what we've been writing about) that is worth exploring (certainly doesn't carry near the amount of stuff Air Raid teams currently do). It isn't necessarily the plays themselves, but how they're packaged together and used as punch and counter-punch diagnosis.

How he teaches "the offense" is evident in what you've seen with Threet and Osweiller. They are lightening quick in throwing 3-step and 5-step that appears brutal on defenses (they know exactly what they are looking for based on the concept and process through it all).

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

Brophy and I are going to be writing more about the offense in weeks to come, but here are few things to keep in mind: Mazzone wants to stress the defense's perimeter fulcrum. Watch the USC game; I don't think I have ever scene such transparent objectives in my life; they are constantly trying to widen the defense. When they widen the edge their inside zone game become effective, but you need to remember that it's not a real rugged zone game; they don't do combos and stuff; its only effective if they have one on one matchups. But stretching the defense horizontally also helps his vertical game, because it transforms zone into man.

The thing to remember is this too: they really only carry a few concepts every game, especially in their dropback package. More later...

The thing to remember about their zone game is this: it's bang or bust; if they don't win their individual matchups the play goes no where. Think about some the idiotic comments that Rod Gilmore made the other night. It asked why on second and ten did Mazzone run what he described as an "inside handoff" that went for nothing. Well, it was the right call for the front; they had the numbers to win but simply did not on that play. I like to think of it as "scat" zone. I know that sounds odd, but it's not an inside zone in the Alex Gibbs, Eliot Uzelac sense.

In a lot of ways I think that Mazzone is reviving some old things that Purdue did once upon a time. Think of how he motions his backs; it reminds me of how Purdue, WAZZU, and for that matter Miami of yesterday all motioned to empty as a way of stretching the defense's flanks in order to create windows underneath, but also to put backers and backs on virtual islands.

Also, think of how they use the bubble. People talk about the bubble as an extended hand off, but most teams really do not throw it well enough for it to be considered their stretch or wide zone play; not the case with ASU. I don't think I've seen a team that can run bubbles with the back, from 2x2, or 3x1 as effectively as they do regardless of the look. In a sense, the bubble is one of their plays that they feel that they can run versus anything to make critical yards, regardless of whether the defense knows what coming or not. Their third scoring drive the other night that came of the Vontez's pick was built almost entirely of of bubbles in one form or another.

Chris is right, there is nothing radical about what their doing. We will cover this in a post later in the season, but the one thing that they have done better than just about anybody is to accelerate the speed of their vertical game; when their on their game they throw verticals just as fast as quicks.

Yeah, in a sense it really is just that - big on big; they never really get to the second level; basically, its the back's responsibility to make the backer miss, which is what happens when they get big plays out of their zone game.

In terms of packages they carry, if you watch them closely they basically run four concepts from 2x2 and 3x1: Snag; 4 Verts, Y Cross, and Drive or Shallow. Not a huge Smash team in the conventional sense; when they hit the corner its coming off their 3-man snag a lot.

That said, they do tag the backside with a number of different combos, such as double post, post corner, Dig choice, etc.

Its really about an Economy of Concepts

If you're horizontally stretching a defense and emptying the box (to run.....and run easy) I suppose it isn't necessary to mash and bang with getting vertical movement on IZ and working combos (still not sure if I swallow this just yet) them running IZ will blow your mind ("wtf are they doing!?!") if you're accustomed to how IZ is traditionally run out of 1 back.

watch how they 'zone' against a 3man front....not what you'd think

I would say that Alex Gibbs' one-cut rule is central to the success of the play in for Mazzone's back because of the nature of their scheme, which in part why the back aligns on the QB's heel rather than simply adjacent to him as he does in other zone gun schemes, such as Northwestern's, for example.

To build on Brophy's point, motion is used here in much the same way as it was used back in the day at Wyoming, Purdue, WAZZU, etc. Yes, it definately clarifies the read for the QB in that it tells him right away which side of the field he's going to work, especially in the Snag game, but it also is a way of putting extreme pressure on the number four to that side, the defense's fulcrum. It's another way of "controlling" this guy and making sure that he is out of the box, that he does not become a 1/5 player in the box.

Though most applications of ASU's offense are pretty basic in each game, the quirks against Oregon would be apparent for most coaches. Whereas most 7-man front defenses, Mazzone can pretty much give his quarterback a very clear picture. With Oregon's nickel/dime (2/1 DL) the picture was extremely cloudy with linebackers and safeties dropping into overhang positions. The heavy use of motion in that game was a product of getting Oregon to declare what they were truly running (where the safeties had to be.....and would the out-leverage themselves from helping their corners against the larger receivers). On the swing, it would primarily require the safety to make the stop because they were playing a heavy dose of C5 and rushing 4 or fire zoning and rushing 5.

What is interesting for coaches, was how Mazzone's system could adapt to it without losing it's shit. Facing something that was as different and that could get into and out of box threats pretty easy (from depth), ASU didn't have to do anything outside of themselves to handle it. With so many defenders outside the tackles on each snap, Oregon really was daring them to run inside and how ASU was hammering the flare/swing to open up the inside. If they threw the swing, it was going to have to be a safety to stop it (leaving X/Z pretty much 1-on-1) . I didn't find many times where Oregon didn't bring 5 every down, so it made the dig/shallow read pretty easy (either the WLB/MLB was widening for the swing or were both dropping to hook) .

What should be interesting for COACHES is not what they are doing but how they are processing the information on the field. Just by segmenting the defense, picking on one particular defender they can make some pretty safe assumptions on where everyone else will fit and who becomes the best ball carrier in that situation.

I think what we have to remember is that all spread offensive systems strive in some way or another to displace defenders and in the process place an inordinate amount of structural stress on the defense's force or alley players. Whether it's RichRod's spread option or Noel Mazzone's version, both offenses are really trying to hammer on a defenses adjuster backer, which in most 2 hi looks is going to be the sam, at least most of the time. RichRod does it with the Zone Read and Zone Bubble, as we've seen in the excellent talks that Brophy has posted on the blog. For Rich, it's really about trying to make sure that the adjuster never gets into the box, he's the guy they need to control. Mazzone too wishes to attack the adjuster, but his objectives are little different; yes, he wants to run inside zone, but, as Brophy noted, it's really more about identifying the defense's anchor player in order to diagnose not the scheme in general, but more importantly, the defense's individual matches, which, if you think about it, in the era of match-zone is more important than ever.

In a sense, it shows how motion is being used again not so much as a way of gaining mismatches and what not, the offense's general scheme already takes care of that, but of diagnosing what it is that the defense is doing. So, in a way, it just shows how we are coming full circle with the spread. Motion that was once jettisoned is now coming back as a tool for identifying a defenses seams and stress points.

Also, as was noted above, motion is not used blindly by Mazzone. In the Missouri game they hardly used motion because MU is fairly straightforward structurally; with Oregon, however, it was necessary.

With this in mind and to serve as a type of sidebar edification on the matter, we’re “reposting” an exchange offered by hemlock and I on COACHHUEY (explaining Mazzone’s system). So not to break the flow of dialogue (or require any actual work on my part) I’m leaving the posts as-is in the sequence they occured . Hemlock’s thoughtful prose and profound commentary is in gold, while my rambling gibberish is in diarrhea green.

** I realize some of the video (through Vimeo) hosted here is hard to come by. If you are not aware of how to rip flash already, I’ll direct you to use Firefox and download the video add-on. Start a video, then enable the download (and its yours).

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.

Noel Mazzone is Noel Mazzone. He has always been 1-back. What he's doing in Arizona, is essentially what he's always done, having evolved it through the years.It IS zone-read, but its all controlled/filtered through a systematic way of horizontally stretching the defense, while at the core being vertically orientated (zone-read, F swing, Stick/Snag/Scat/Drive/Shallows/Verts/and tons of screens). There is an efficiency in his application (which is what we've been writing about) that is worth exploring (certainly doesn't carry near the amount of stuff Air Raid teams currently do). It isn't necessarily the plays themselves, but how they're packaged together and used as punch and counter-punch diagnosis.

How he teaches "the offense" is evident in what you've seen with Threet and Osweiller. They are lightening quick in throwing 3-step and 5-step that appears brutal on defenses (they know exactly what they are looking for based on the concept and process through it all).

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.

I would resist calling Mazzone's offense an extension of the pro-single back. If the source of this thought is Mazzone's stint with the Jets in the NFL then I think it a little off. Too me it's evident that Mazzone went to the NFL not to make that his final destination but as a sort of intense sabbatical in that he went there to see what that game had to teach him. I think his goal was always to get back to the college game.Brophy and I are going to be writing more about the offense in weeks to come, but here are few things to keep in mind: Mazzone wants to stress the defense's perimeter fulcrum. Watch the USC game; I don't think I have ever scene such transparent objectives in my life; they are constantly trying to widen the defense. When they widen the edge their inside zone game become effective, but you need to remember that it's not a real rugged zone game; they don't do combos and stuff; its only effective if they have one on one matchups. But stretching the defense horizontally also helps his vertical game, because it transforms zone into man.

The thing to remember is this too: they really only carry a few concepts every game, especially in their dropback package. More later...

The thing to remember about their zone game is this: it's bang or bust; if they don't win their individual matchups the play goes no where. Think about some the idiotic comments that Rod Gilmore made the other night. It asked why on second and ten did Mazzone run what he described as an "inside handoff" that went for nothing. Well, it was the right call for the front; they had the numbers to win but simply did not on that play. I like to think of it as "scat" zone. I know that sounds odd, but it's not an inside zone in the Alex Gibbs, Eliot Uzelac sense.

In a lot of ways I think that Mazzone is reviving some old things that Purdue did once upon a time. Think of how he motions his backs; it reminds me of how Purdue, WAZZU, and for that matter Miami of yesterday all motioned to empty as a way of stretching the defense's flanks in order to create windows underneath, but also to put backers and backs on virtual islands.

Also, think of how they use the bubble. People talk about the bubble as an extended hand off, but most teams really do not throw it well enough for it to be considered their stretch or wide zone play; not the case with ASU. I don't think I've seen a team that can run bubbles with the back, from 2x2, or 3x1 as effectively as they do regardless of the look. In a sense, the bubble is one of their plays that they feel that they can run versus anything to make critical yards, regardless of whether the defense knows what coming or not. Their third scoring drive the other night that came of the Vontez's pick was built almost entirely of of bubbles in one form or another.

Chris is right, there is nothing radical about what their doing. We will cover this in a post later in the season, but the one thing that they have done better than just about anybody is to accelerate the speed of their vertical game; when their on their game they throw verticals just as fast as quicks.

Yeah, in a sense it really is just that - big on big; they never really get to the second level; basically, its the back's responsibility to make the backer miss, which is what happens when they get big plays out of their zone game.

In terms of packages they carry, if you watch them closely they basically run four concepts from 2x2 and 3x1: Snag; 4 Verts, Y Cross, and Drive or Shallow. Not a huge Smash team in the conventional sense; when they hit the corner its coming off their 3-man snag a lot.

That said, they do tag the backside with a number of different combos, such as double post, post corner, Dig choice, etc.

Its really about an Economy of Concepts

If you're horizontally stretching a defense and emptying the box (to run.....and run easy) I suppose it isn't necessary to mash and bang with getting vertical movement on IZ and working combos (still not sure if I swallow this just yet) them running IZ will blow your mind ("wtf are they doing!?!") if you're accustomed to how IZ is traditionally run out of 1 back.

watch how they 'zone' against a 3man front....not what you'd think

I would say that Alex Gibbs' one-cut rule is central to the success of the play in for Mazzone's back because of the nature of their scheme, which in part why the back aligns on the QB's heel rather than simply adjacent to him as he does in other zone gun schemes, such as Northwestern's, for example.

Against Oregon, the ASU offense relied heavily on motioning the H or Z into the formation. They barely used motion against Missouri. It is only used to make a more decisive read for the throw (remove a defender from the running lane).

Though most applications of ASU's offense are pretty basic in each game, the quirks against Oregon would be apparent for most coaches. Whereas most 7-man front defenses, Mazzone can pretty much give his quarterback a very clear picture. With Oregon's nickel/dime (2/1 DL) the picture was extremely cloudy with linebackers and safeties dropping into overhang positions. The heavy use of motion in that game was a product of getting Oregon to declare what they were truly running (where the safeties had to be.....and would the out-leverage themselves from helping their corners against the larger receivers). On the swing, it would primarily require the safety to make the stop because they were playing a heavy dose of C5 and rushing 4 or fire zoning and rushing 5.

What is interesting for coaches, was how Mazzone's system could adapt to it without losing it's shit. Facing something that was as different and that could get into and out of box threats pretty easy (from depth), ASU didn't have to do anything outside of themselves to handle it. With so many defenders outside the tackles on each snap, Oregon really was daring them to run inside and how ASU was hammering the flare/swing to open up the inside. If they threw the swing, it was going to have to be a safety to stop it (leaving X/Z pretty much 1-on-1) . I didn't find many times where Oregon didn't bring 5 every down, so it made the dig/shallow read pretty easy (either the WLB/MLB was widening for the swing or were both dropping to hook) .

What should be interesting for COACHES is not what they are doing but how they are processing the information on the field. Just by segmenting the defense, picking on one particular defender they can make some pretty safe assumptions on where everyone else will fit and who becomes the best ball carrier in that situation.

I think what we have to remember is that all spread offensive systems strive in some way or another to displace defenders and in the process place an inordinate amount of structural stress on the defense's force or alley players. Whether it's RichRod's spread option or Noel Mazzone's version, both offenses are really trying to hammer on a defenses adjuster backer, which in most 2 hi looks is going to be the sam, at least most of the time. RichRod does it with the Zone Read and Zone Bubble, as we've seen in the excellent talks that Brophy has posted on the blog. For Rich, it's really about trying to make sure that the adjuster never gets into the box, he's the guy they need to control. Mazzone too wishes to attack the adjuster, but his objectives are little different; yes, he wants to run inside zone, but, as Brophy noted, it's really more about identifying the defense's anchor player in order to diagnose not the scheme in general, but more importantly, the defense's individual matches, which, if you think about it, in the era of match-zone is more important than ever.

In a sense, it shows how motion is being used again not so much as a way of gaining mismatches and what not, the offense's general scheme already takes care of that, but of diagnosing what it is that the defense is doing. So, in a way, it just shows how we are coming full circle with the spread. Motion that was once jettisoned is now coming back as a tool for identifying a defenses seams and stress points.

Also, as was noted above, motion is not used blindly by Mazzone. In the Missouri game they hardly used motion because MU is fairly straightforward structurally; with Oregon, however, it was necessary.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Protecting Against Risk: Iowa State

This is usually a weird time of year for most programs. The season has ended and now your Saturdays exist in unmetered time with no pressing needs to breakdown the next opponent. No more cramming as much as you can into your day to make sure no stone is left unturned to find a competitive edge. Now, all you can do is build for the future and remain hopeful in your underclassmen while you cycle through the flashbacks of your season. This dead silence at the end of the year always comes suddenly, leaving us asking, “Now what”?

It is this time of the “season” that we can take a step back and slow down without consequence. When under the deadline of the season, there is little time for introspection or second-guessing. So now that we aren’t faced with the task of treading water, what would be the best use of your staff’s time? It isn’t researching a new scheme, installing new plays, or trying to innovate a new clinic talk. This off-season, try re-evaluating the efficiency of your offense. Rather than making things more difficult by adding plays, find ways to simply reduce the risk within your scheme. How can you protect your core plays to that defenses can’t simply take them away?

A case in point we can use is the I-35 shocker in Ames this past Friday. While exciting, I’d hardly call a game with 8 turnovers (and countless miscues) “great”. However, the game did provide a decent exercise in risk management for Iowa State. Oklahoma State is one of the best teams in college football this year and truly outmatched the Cyclones in every area. What aided Iowa State in the overtime victory wasn’t necessarily certain plays, but how their system allowed them to play within themselves and maintain their comfort zone.

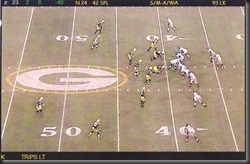

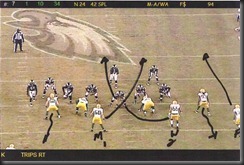

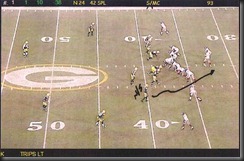

With Freshman quarterback, Jared Barnett, the Cyclone offense could keep his workload light through a minimalistic approach of moving the football. Much like the modular approach of Noel Mazzone we’ve discussed before, the Cyclones were going to run zone and zone-read to establish their inside run game. They protected this series through KEY (flash) and MICKEY (flash draw) on the perimeter. The rationale is, a defense can either put 6 in the box to even up on the perimeter (put them in a better position against the flash screen) and be vulnerable to frontside zone or a backside keep. If a defense loads the box with 7 defenders to take away your zone and zone-read game, they open themselves up to an explosive play by a free receiver on the perimeter (see the comments section of Mazzone Revisited).

If these plays are just viewed by themselves, they aren’t all that sexy, and are quite cheap. What is particularly interesting about this pairing and witnessing it in this game, was how ineffective they were early in the game (particularly the key screens). Tom Herman and staff stuck to the game plan and used these plays to diagnose the appropriate response, leaving little responsibility to burden their young quarterback with. Because they continued to stick with the formula (inside-outside-inside compliments), they were able to slow down an athletically superior defense and open them to this horizontal stretch of the field throughout the game, climaxing in the 2nd Overtime ( 3 successive inside zone runs) for the win.

It is this time of the “season” that we can take a step back and slow down without consequence. When under the deadline of the season, there is little time for introspection or second-guessing. So now that we aren’t faced with the task of treading water, what would be the best use of your staff’s time? It isn’t researching a new scheme, installing new plays, or trying to innovate a new clinic talk. This off-season, try re-evaluating the efficiency of your offense. Rather than making things more difficult by adding plays, find ways to simply reduce the risk within your scheme. How can you protect your core plays to that defenses can’t simply take them away?

A case in point we can use is the I-35 shocker in Ames this past Friday. While exciting, I’d hardly call a game with 8 turnovers (and countless miscues) “great”. However, the game did provide a decent exercise in risk management for Iowa State. Oklahoma State is one of the best teams in college football this year and truly outmatched the Cyclones in every area. What aided Iowa State in the overtime victory wasn’t necessarily certain plays, but how their system allowed them to play within themselves and maintain their comfort zone.

With Freshman quarterback, Jared Barnett, the Cyclone offense could keep his workload light through a minimalistic approach of moving the football. Much like the modular approach of Noel Mazzone we’ve discussed before, the Cyclones were going to run zone and zone-read to establish their inside run game. They protected this series through KEY (flash) and MICKEY (flash draw) on the perimeter. The rationale is, a defense can either put 6 in the box to even up on the perimeter (put them in a better position against the flash screen) and be vulnerable to frontside zone or a backside keep. If a defense loads the box with 7 defenders to take away your zone and zone-read game, they open themselves up to an explosive play by a free receiver on the perimeter (see the comments section of Mazzone Revisited).

If these plays are just viewed by themselves, they aren’t all that sexy, and are quite cheap. What is particularly interesting about this pairing and witnessing it in this game, was how ineffective they were early in the game (particularly the key screens). Tom Herman and staff stuck to the game plan and used these plays to diagnose the appropriate response, leaving little responsibility to burden their young quarterback with. Because they continued to stick with the formula (inside-outside-inside compliments), they were able to slow down an athletically superior defense and open them to this horizontal stretch of the field throughout the game, climaxing in the 2nd Overtime ( 3 successive inside zone runs) for the win.

Friday, November 4, 2011

More Running from the Gun: Robert McFarland

Thursday, October 27, 2011

Air Raid Adaptation (cont'd)

We've covered this before quite a bit and Chris Brown knocks it out of the park when writing about the loaded backfield of Oregon and West Virginia but just documenting the trend that many teams are featuring heavy backfields out of the same "spread" 10 personnel groupings.

It goes to show that everything is cyclical and if you stay in the same spot (schematically) all you become is a stationary target.

On a somewhat personal note, I find you can discover so much more about actual 'coaching' from the programs that have to fight for wins. It takes creativity, some guile, and a lot of hustle to manufacture plays that add up to wins when you're playing with a short deck. While Tony Franklin will never be considered a face for the public, there is no denying his commitment to his players and his humble desire to win. An interesting note to the season for La Tech is how much their offensive staff (in their first real season after recruiting) is relying on brand new faces to the program. With transfers (WR) Quinton Patton and (OT) Oscar Johnson, to true freshmen (QB) Nick Isham, (RB) Ray Holley and (RB) Hunter Lee getting the bulk of responsibility in the past four weeks.

Since most nickel packages don't bother repping 2-back looks (simply because you'll be in base defense vs 21), a spread offense that lives in the 3x1 and 2x2 world can completely ham-fist the defensive personnel on the field when seeing power formations such as this.

Although an adaptation of the TFS since about 2007 (Brown/Black gun), the use of essentially 3-backs here by Louisiana Tech against a sound Utah State is exactly the same look they showed Mississippi State, with the exception of the tight end being replaced (and Franklin inserts a linebacker as a lead blocker).

It goes to show that everything is cyclical and if you stay in the same spot (schematically) all you become is a stationary target.

On a somewhat personal note, I find you can discover so much more about actual 'coaching' from the programs that have to fight for wins. It takes creativity, some guile, and a lot of hustle to manufacture plays that add up to wins when you're playing with a short deck. While Tony Franklin will never be considered a face for the public, there is no denying his commitment to his players and his humble desire to win. An interesting note to the season for La Tech is how much their offensive staff (in their first real season after recruiting) is relying on brand new faces to the program. With transfers (WR) Quinton Patton and (OT) Oscar Johnson, to true freshmen (QB) Nick Isham, (RB) Ray Holley and (RB) Hunter Lee getting the bulk of responsibility in the past four weeks.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

Rich Rodriguez Spread Offense

Like the Calvin Magee clinic? How about hearing from the man himself, Rich Rodriguez?

Six more hours of spread offense dissection from one of the decade’s biggest names. This clinic took place just before Rodriguez took over at West Virginia while he was making a name for himself under Tommy Bowden at Clemson.

While nothing went according to plan at Michigan, the innovations Rodriguez spearheaded at Tulane, Clemson, and finally West Virginia, became his thumbprint on many offenses we’re seeing today (particularly in the run game). What if Rich Rod stayed at WVU instead of trying to resurrect Michigan? What if they actually landed Terrelle Pryor in 2008 instead of having to pin their last desperate hopes on Denard Robinson? UM’s defense certainly didn’t help matters, but it makes for an interesting look at how drastically perceptions would change if a few chance events took place.

In the late 90s, while other programs were rediscovering athleticism at quarterback (McNabb at Syracuse / Vick at Va Tech), Rodriguez was capturing lightning in a bottle by paring athletes (Shaun King, Woody Dantzler) with complimentary, multiple option threats from the gun. If you have the old (now canonized) Alex Gibbs Gilman clinic on wide-zone, you’ll hear Gibbs marvel over what kind of mileage coaches were getting out of Dantzler at the time. In the infancy of his philosophy, it was applying extremely simple concepts from the gun and capitalizing on the low-hanging fruit of “athletes in space”. It was by adapting to the talent on the roster to the innovations of defensive adjustments, borrowing from other successful programs (Northwestern), and acquiring an infusion of expertise (Rick Trickett), that Rodriguez became increasingly successful through the height of his career.

Rodriguez essentially set the table for up-tempo offenses of today (Oregon, Oklahoma State, etc) that have taken the best of both worlds (spread option with proven Air Raid concepts) and evolved into a multi-dimensional threat to defenses. Did Rodriguez plateau or hit the creative wall before leaving WVU? The offense relied heavily on zone read and speed option with the passing game usually a result of play-action or a simplified 2-man-game. Was he the victim of a program in decline, a dried up well (little recruiting help), or did his offense simply fail to evolve itself to the defense’s natural response? Will we witness his return to the coaching ranks, adapting his offense to the new decade’s defenses?

Six more hours of spread offense dissection from one of the decade’s biggest names. This clinic took place just before Rodriguez took over at West Virginia while he was making a name for himself under Tommy Bowden at Clemson.

While nothing went according to plan at Michigan, the innovations Rodriguez spearheaded at Tulane, Clemson, and finally West Virginia, became his thumbprint on many offenses we’re seeing today (particularly in the run game). What if Rich Rod stayed at WVU instead of trying to resurrect Michigan? What if they actually landed Terrelle Pryor in 2008 instead of having to pin their last desperate hopes on Denard Robinson? UM’s defense certainly didn’t help matters, but it makes for an interesting look at how drastically perceptions would change if a few chance events took place.

In the late 90s, while other programs were rediscovering athleticism at quarterback (McNabb at Syracuse / Vick at Va Tech), Rodriguez was capturing lightning in a bottle by paring athletes (Shaun King, Woody Dantzler) with complimentary, multiple option threats from the gun. If you have the old (now canonized) Alex Gibbs Gilman clinic on wide-zone, you’ll hear Gibbs marvel over what kind of mileage coaches were getting out of Dantzler at the time. In the infancy of his philosophy, it was applying extremely simple concepts from the gun and capitalizing on the low-hanging fruit of “athletes in space”. It was by adapting to the talent on the roster to the innovations of defensive adjustments, borrowing from other successful programs (Northwestern), and acquiring an infusion of expertise (Rick Trickett), that Rodriguez became increasingly successful through the height of his career.

Rodriguez essentially set the table for up-tempo offenses of today (Oregon, Oklahoma State, etc) that have taken the best of both worlds (spread option with proven Air Raid concepts) and evolved into a multi-dimensional threat to defenses. Did Rodriguez plateau or hit the creative wall before leaving WVU? The offense relied heavily on zone read and speed option with the passing game usually a result of play-action or a simplified 2-man-game. Was he the victim of a program in decline, a dried up well (little recruiting help), or did his offense simply fail to evolve itself to the defense’s natural response? Will we witness his return to the coaching ranks, adapting his offense to the new decade’s defenses?

Most of the second session illustrates what Rodriguez was doing at Clemson. Since part of this discussion relates to how that offense changed through the decade, here is some supporting evidence:

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Quarterbacking with Jim Miller

A collection of quarterback fundamentals with Jim Miller, the grittiest of the gritty. Grab your pain meds and enjoy these drills from the Michigan State staff and Chicago’s John Shoop.

For the best quarterback instruction, it begins and ends with Darin Slack C4 Method.

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Calvin Magee: Rodriguez Spread Offense

It wasn’t long ago that the West Virginia football program was known for an entirely different high-octane offense. That offense was spearheaded by a coach who is now deemed a pariah after languishing at Michigan for the past few years. Rich Rodriguez used this simple brand of fast-paced-spread to pressure defenses during his stops at Glenville State, Tulane, Clemson and West Virginia.

Now at Pittsburgh, Calvin Magee was an integral part in developing this ‘spread to run’ offense that Rodriguez became renowned for. In his own words and philosophy, here are 5 hours worth……

Saturday, September 24, 2011

Air Raid Wrinkle (Part II)

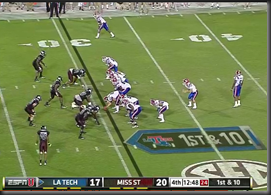

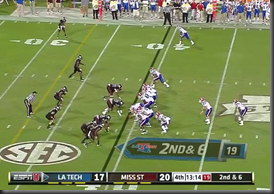

A valiant effort by Louisiana Tech against formerly ranked Mississippi State, coming up short in overtime.

Something new Tony Franklin used in this game was an unbalanced trey 2-back look (like Heavy Over, but from the gun and H is off).

Franklin ran power, counter, and reverse out of this set……

and ended up setting up a huge 3rd down conversion in the 4th quarter running 51 Solid off of Rodeo action (02:34:52 of broadcast).

Though they lost, the 17 year old quarterback Isham produced in the passing game using Stick, Levels, Drive, and Y Cross (end of regulation interception in the end zone) even with the running back injured (Creer) and the multi-purpose H-back (Holley) out for the game. On the final interception, needing to inch closer to convert the downs (5 yards), likely because of the inconsistent short-yardage production from the banged up Lennon Creer, Tech opts for Y Cross isolating standout receiver, Quinton Patton, in the boundary with a double outlet underneath to the field. Mississippi State presses the line of scrimmage showing press cover 1, essentially baiting Isham to throw the 1-on-1 with Patton. At the snap, MSU bails out to cover 3, Patton's cornerback retreats deep with deep help from the free safety in the end zone. Because MSU disguised this so well (discouraging the run with 7 defenders versus the 5 blockers), it was too late for Isham to recognize the Hi-Lo on the lone MSU linebacker to the field.

The rebroadcast can be seen at the link below

http://espn.go.com/watchespn/player/_/source/espn3/id/226926/

Something new Tony Franklin used in this game was an unbalanced trey 2-back look (like Heavy Over, but from the gun and H is off).

Franklin ran power, counter, and reverse out of this set……

and ended up setting up a huge 3rd down conversion in the 4th quarter running 51 Solid off of Rodeo action (02:34:52 of broadcast).

Though they lost, the 17 year old quarterback Isham produced in the passing game using Stick, Levels, Drive, and Y Cross (end of regulation interception in the end zone) even with the running back injured (Creer) and the multi-purpose H-back (Holley) out for the game. On the final interception, needing to inch closer to convert the downs (5 yards), likely because of the inconsistent short-yardage production from the banged up Lennon Creer, Tech opts for Y Cross isolating standout receiver, Quinton Patton, in the boundary with a double outlet underneath to the field. Mississippi State presses the line of scrimmage showing press cover 1, essentially baiting Isham to throw the 1-on-1 with Patton. At the snap, MSU bails out to cover 3, Patton's cornerback retreats deep with deep help from the free safety in the end zone. Because MSU disguised this so well (discouraging the run with 7 defenders versus the 5 blockers), it was too late for Isham to recognize the Hi-Lo on the lone MSU linebacker to the field.

http://espn.go.com/watchespn/player/_/source/espn3/id/226926/

Greg Studrawa: Zone from the Gun

Thursday, September 22, 2011

Catch-Man Technique

As defenses adapted through the 90s and offenses began finding more and more success passing the football, zone defenses were forced to evolve to pattern-matching routes. Matching out of zone with six defenders would leave an extra hole player against five receivers. The natural progression from this was the fire-zone, adding a zone defender to an overloaded pressure while accounting for all receivers. Fire-zoning became (and continues to be) a catch-all solution with static pre-snap defensive looks. The only issue would be the ability to retain alignment leverage without giving away your intentions For this reason, fire-zones are largely packaged by field and boundary rather than strength of formation.

So what would be the next step for defenses to get a jump on playing a variety of routes while providing the capability of overloaded pressure? In the perfect world, the defense that could ensure it:

- retained its pre-snap coverage shell (consistent look)

- got the favorable personnel matchup

- was able to generate an overload pressure on the passer

A defense that could do that would be able to hold the chalk last in this new age of offensive football. "Catch Man" or "off-man" coverage means exactly that; the defensive backs catch the route as it develops. Because this 'catch' won't happen until well into the route, the overall defense can assume any shape/structure (1-high / 2-high) it wants without giving many pre-snap clues to the offense. From basic pre-snap zone looks, the defense could be fire-zoning or playing man and very likely will be bringing pressure, but from where?

This ‘answer’ kind of becomes a full-circle evolution, where many successful defenses are returning to a formula that was relied upon 30 years ago. It isn’t surprising that the leaders of catch-man defenses are protégés of the Buddy Ryan school of defense (Gregg Williams, Rex Ryan, Rob Ryan, Dom Capers) of the 80s. Many of the more advanced elements of Buddy Ryan's late 80's-era 46 defenses (catch man, loaded coverage, fire-zones, swipe/thumb coverage, and a reliance on man-free) are what is now en vogue in today's game. This wide array of skill sets also begets a need to include multi-functional personnel on the field, where a 3-man fronts (or less) are preferred (see psycho posts).

In this post, we’ll try to provide some coaching insight into developing the skills for effective catch-man coverage. This concept was admittedly difficult for me to get comfortable with many years ago, as I really believed in the old bump-and-run technique of man coverage. I felt that you had to immediately disrupt routes and out-leverage a receiver before he even began his release. While there are benefits to holding up receiver stems and immediate reroutes, there is limited flexibility in adapting to formations using this technique. The effectiveness of press can be diminished with pre-snap movement from the offense. With catch-man, you can get the best of both worlds because the coverage structure remains consistent, you can effectively play quick and deep passing game, while still disrupting receiver stems.

Added for illustration purposes, this Revis 1-on-1 footage highlights how to leverage a receiver from many different alignments (some off, some press but they all essentially turn into the same type of coverage by the time the receiver makes his break).

With the help of video, I hope to illustrate some of the techniques and methods of leveraging routes from an “off” alignment. The skill sets used for catch-man are also helpful in other coverage (press man / pattern-match) techniques, so using these drills will have carry-over (high ROI) for your secondary. The depth of alignment for the defensive back usually starts at 8 yards. From this depth, a defender could essentially stay put and the receiver would likely make his break in front of the defender. As the player gains more confidence (athletic ability allowing), this pre-snap cushion can be shortened and stemmed in and out of. The beauty of this is that just aligning in the path of a receiver’s stem, the defender has already re-routed the receiver; either the receiver runs over the defender (not conducive to actually running the route) or he is forced to make his break early, declaring how the defender will play the route.

Just like pattern-matching in zone, secondary defenders will play routes based on the drop of the passer, then anticipating route breaks based on a process of elimination. Once the route is identified/confirmed, the defender can jump the interception point or secure the tackle.

Catch-man is best delivered to players by staging teaching into depths of the quarterback drop. Just like pattern-matching, you will get specific routes based on the depth of the drop.

- With quick-step or 3-step (quicks 0-5 yards), a receiver could really only run one of the following routes: Screen, slant, hitch, speed out

- With 5-step routes (intermediate 10-15 yards), the receiver would likely run: out, curl, hook, dig, comeback

- With deeper routes (15+ yards off of 5-7 step drops / sprint out and play-action) you could expect: post, corner, fade wheel

While eyeing the quarterback, the corner will slowly come out of his stance in a crossover step (or backpedal). The key here is for him to remain in control of his body with an arched back with the intent to be able to mirror the receiver perpendicular to the line of scrimmage (inside/outside break under 6 yards). If the receiver stems inside, the corner should laterally step inside to mirror him. Again, it should be stressed that the corner should walk out of his stance, reading the quarterback in slow motion, keeping horizontal leverage on the receiver (mirror him). By using this horizontal leverage, he can easily recognize where the quarterback is going with the ball (based on the angle) and attack the interception point.

If the corners are consistently aligning with 8 yards depth, they will likely see a lot of quick game to attack the cushion. When the receiver breaks under 8 yards, the corner shouldn’t attempt to come underneath the receiver for the interception unless he is certain he can get two hands on the ball. Otherwise, he should look to secure the tackle by coming in low, with arms clubbing up and expanding the receiver’s noose. It should be acknowledged that playing 3-step is difficult. The important thing is that the defender doesn’t give up a double-move or lose the 1-on-1 tackle if the ball is caught. In the event the DB gets beat here, he should cut his loses by collisioning the receiver or actually pulling him down (preventing a sure touchdown).

Once the defender sees the drop is greater than 3-step, he accelerates his pace and immediately snaps to the receiver, keying the inside hip. The defender will then fight for control of the receiver with leverage (either hip-to-hip or at least be at arm’s length). If he loses this control (out-of-phase), the priority is just to catch up to the receiver and never look back. To help against false stepping or getting beat on double-moves, its important to rep receiver jukes, that a cut can only be made when the receiver’s shoulders rise up. Once the DB recognizes the drop is greater than 3-step his thinking is to “slowly absorb the route” and close any air that exists between the receiver and defender. With the accelerated pace of this deeper route, the defender’s concentration should be solely on the receiver’s inside hip. From this point, there is little that differentiates itself from traditional (press) man coverage. The defender should work for total control of the receiver with the progression of “receiver – recognition point (break) – ball”. Only until the receiver is controlled with leverage and the route break is identified, should the defender actually play the ball for the interception. Always finish – play the man, THEN the ball.

Like I said, this will likely be a defensive flavor we’ll see more of in the future and your thoughts and experiences on the matter are certainly welcome. For an added bonus, some more video on leveraging receivers (from a press position, but its all relative). Key points to take note of are the solid base and stuttering of the corner's feet until the receiver truly commits to a release and then the flipping of the hips (and footwork) to maintain the in-phase relationship….

Wednesday, September 14, 2011

WHY NOEL MAZZONE: DENNIS ERICKSON AND THE ONE-BACK SPREAD OFFENSE

Over the course of this summer, Brophy and I have talked a lot of offense. As many of you know, we’ve focused much of our discussion on what Noel Mazzone is doing at Arizona State. And given the richness of this topic, I suspect that we will continue to do so throughout much of this college football season.

For me, perhaps the greatest upshot of these discussions has been the way it took me back in time to when I first got into coaching football. Specifically, it got me thinking about Dennis Erickson and how much I enjoyed watching his offenses at Wyoming, WAZZU, and Miami, which in turn got me to think more critically about his hiring of Noel Mazzone. Sure, Mazzone was one of his guys for a short while at Oregon State, but when Erickson was forced to replace Rich Olsen, he clearly had the pick of the litter. I mean, besides knowing Mazzone, which obviously counts for something, there had to other reasons why he chose him, rather than, let’s say, Dana Holgorsen, or some other hip, en vogue spread offense guru.

I think to get at this problem the right way we have to settle a few things about why Erickson found himself in such a situation in the first place. If we were to blindly swill the pap that ESPN spews, the reason was quite simple: Erickson’s job was on the line and Rich Olsen’s offense was too antiquated for today’s game. Now, I think most readers know where I stand on this matter, but for the sake of posterity, let’s understand that Rich Olson is an outstanding football coach and that the offense he coordinated was not outdated by any stretch of the imagination. The simple fact is that the administration forced Erickson’s hand, so a change had to be made. But this should not be interpreted as the administration taking the keys away from Erickson, because his choice of Mazzone reflects the degree to which, at a deep structural level, Noel’s offensive thinking is predicated upon the same set of fundamental beliefs and values as Erickson’s.

The reason I harp on this is because, and I mean no disrespect here, Mazzone’s incarnation of the spread is so medieval that it’s progressive. By this, I mean that the fundamental principles and structures upon which Mazzone’s offense is predicated are virtually identical to those upon which Erickson based his offenses throughout the 80s and 90s, which is to say – verticals, quicks, and zone running made easy by defensive displacement.

I don’t want to spend too much time on Erickson’s original offense. For those interested, please see Chris Brown’s treatment at Smart Football. The other source to consider is UTEP football, because for all intents and purposes the offense Mike Price runs today is not too terribly different from the one he ran back in the 90s at WAZZU.

With that disclaimer of sorts, I will say a word or two about the spread offense Erickson ran with great success from Idaho and Wyoming to Miami, Oregon State, and, at least initially, Arizona State. For those expecting gaudy route structures, Erickson’s may appear, at least upon first blush, somewhat basic; Erickson really did not rely much on layered concepts, such as Shallow, Drive, Mesh, etc, preferring instead to rely on vertical stem packages in both his quick and drop back games. The reason for this is very simple: Erickson never wanted to stop running the ball; he simply wanted to create defensive structures that would enable him to run the ball effectively inside. This is why Erickson from the very beginning emphasized stretching the defense from sideline to sideline, not only with formations, but concepts as well. Formations and splits that would effectively center the defense by inviting it to align players closely to the LOS were jettisoned in favor of five very basic environments that by alignment would engender some type of a Nickel response.

Diagram I. Tight End / Slot

Diagram II. Trips Closed (TE to the boundary)

Diagram III. Trey

Diagram IV. 3X2 (with Y or T Flexed or in the Slot)

Diagram V. 3X2 (with Y in the Formation)

And because Erickson never wanted to bring the defense towards the ball, his passing game, by design, was designed to create an environment that would stretch the field horizontally, which he would then attack vertically. Consequently, Erickson eschewed routes that could possibly negate the horizontal stretch of his formations, for those that would always “push” the defense off the ball, creating even more vertical space between it and the offense.

Does this mean that Erickson’s one-back was not a ball-control offense, that it was always trying to go for the deep shot? No, only that he sought a way of throwing the ball that would not draw the defense towards the formation, and thus, towards the ball. As a result, what you see is a pass offense based around vertical stems, be they seams and benders, or option routes paired with posts and digs over top.

For me, perhaps the greatest upshot of these discussions has been the way it took me back in time to when I first got into coaching football. Specifically, it got me thinking about Dennis Erickson and how much I enjoyed watching his offenses at Wyoming, WAZZU, and Miami, which in turn got me to think more critically about his hiring of Noel Mazzone. Sure, Mazzone was one of his guys for a short while at Oregon State, but when Erickson was forced to replace Rich Olsen, he clearly had the pick of the litter. I mean, besides knowing Mazzone, which obviously counts for something, there had to other reasons why he chose him, rather than, let’s say, Dana Holgorsen, or some other hip, en vogue spread offense guru.

I think to get at this problem the right way we have to settle a few things about why Erickson found himself in such a situation in the first place. If we were to blindly swill the pap that ESPN spews, the reason was quite simple: Erickson’s job was on the line and Rich Olsen’s offense was too antiquated for today’s game. Now, I think most readers know where I stand on this matter, but for the sake of posterity, let’s understand that Rich Olson is an outstanding football coach and that the offense he coordinated was not outdated by any stretch of the imagination. The simple fact is that the administration forced Erickson’s hand, so a change had to be made. But this should not be interpreted as the administration taking the keys away from Erickson, because his choice of Mazzone reflects the degree to which, at a deep structural level, Noel’s offensive thinking is predicated upon the same set of fundamental beliefs and values as Erickson’s.

The reason I harp on this is because, and I mean no disrespect here, Mazzone’s incarnation of the spread is so medieval that it’s progressive. By this, I mean that the fundamental principles and structures upon which Mazzone’s offense is predicated are virtually identical to those upon which Erickson based his offenses throughout the 80s and 90s, which is to say – verticals, quicks, and zone running made easy by defensive displacement.

I don’t want to spend too much time on Erickson’s original offense. For those interested, please see Chris Brown’s treatment at Smart Football. The other source to consider is UTEP football, because for all intents and purposes the offense Mike Price runs today is not too terribly different from the one he ran back in the 90s at WAZZU.

With that disclaimer of sorts, I will say a word or two about the spread offense Erickson ran with great success from Idaho and Wyoming to Miami, Oregon State, and, at least initially, Arizona State. For those expecting gaudy route structures, Erickson’s may appear, at least upon first blush, somewhat basic; Erickson really did not rely much on layered concepts, such as Shallow, Drive, Mesh, etc, preferring instead to rely on vertical stem packages in both his quick and drop back games. The reason for this is very simple: Erickson never wanted to stop running the ball; he simply wanted to create defensive structures that would enable him to run the ball effectively inside. This is why Erickson from the very beginning emphasized stretching the defense from sideline to sideline, not only with formations, but concepts as well. Formations and splits that would effectively center the defense by inviting it to align players closely to the LOS were jettisoned in favor of five very basic environments that by alignment would engender some type of a Nickel response.

Diagram II. Trips Closed (TE to the boundary)

Diagram III. Trey

Diagram IV. 3X2 (with Y or T Flexed or in the Slot)

Diagram V. 3X2 (with Y in the Formation)

And because Erickson never wanted to bring the defense towards the ball, his passing game, by design, was designed to create an environment that would stretch the field horizontally, which he would then attack vertically. Consequently, Erickson eschewed routes that could possibly negate the horizontal stretch of his formations, for those that would always “push” the defense off the ball, creating even more vertical space between it and the offense.

Does this mean that Erickson’s one-back was not a ball-control offense, that it was always trying to go for the deep shot? No, only that he sought a way of throwing the ball that would not draw the defense towards the formation, and thus, towards the ball. As a result, what you see is a pass offense based around vertical stems, be they seams and benders, or option routes paired with posts and digs over top.

Now, before continuing, I want to head a potential problem off at the pass: rightfully, many coaches would look at this and say that without an aggressive shallow or drive game, how did he manage to control the linebackers? After all, this is essentially the problem Northwestern had a decade ago after their first big year in the spread offense; they had a half-field passing game to either side of the formation, but with nothing over the middle because of wide splits their receivers took. For this, much more so than Northwestern, Erickson used option routes that effectively prevented the linebackers from providing hard and aggressive run support.

So what does any of this have to do with Noel Mazzone? I think what we need to remember is that for a while, and even recently, when coaches hear Mazzone’s name they equate it not just with Snag, but with shallows and other layered concepts. And there is undoubtedly a great deal of truth to this, because for a while shallows and crossers were the bread and butter staples of any Mazzone offense; and while he recognized the need to get vertical even then to prevent people from squatting on his underneath stuff, it was, as will be covered in a future post, usually paired on the back side of his shallows. But shallows are not what characterize Arizona State’s current offense; in fact, one can say that while shallows and drives remain an important part of Mazzone’s current offense, they now play a decidedly more secondary role to his Arizona State’s Vertical game. And this is why, I think, Mazzone was so attractive to Erickson, because Mazzone’s current offensive thinking, from the role formations and verticals, to a simple, yet effective inside zone running game, effectively is entirely in synch with Erickson’s base offensive values.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)