The point of this post will be to illustrate the flexibility the concept provides where most blitzes would ‘break’ or require a check out of. We will concentrate on how coverage defenders should respond to challenging patterns from typically stressful formations of 1-back and empty. This is an element that we enjoy discussing here; the evolution and adaptations within the game of football.

The key to the success of this type of defensive application remains the teaching methodology that carries concepts over from Cover 1, to Cover 3 pattern match, to Rip/Liz match. The combination of these fundamentals are what the success of the fire zone is built upon. Neglecting or not thoroughly teaching the roles will limit the effectiveness of how players operate within the fire zone.

For the sake of discussion, we’ll narrow the application to the “NCAA Blitz” fire zone that everyone runs, but keep in mind, just plug-and-play personnel groupings because it’s all relative regardless if it is a safety, backer, or lineman taking on the role of one of the underneath defenders. For the sake of clarity in this review, terminology varies from staff to staff, but I will refer to the wall/flat player as the ”SCIF” player and the middle hole/hook player as the “final 3rd” defender.

As we’ve discussed before, any defense can line up against 2-back pro formation, it’s what the defense has to become when confronted by 2x2 or 3x1 sets that determines what the defense actually is.

The best way to conceptualize the coverage matching is that you will zone into the pressure / man (match) away from the blitz.

2 x 2

With the fire zone you’re essentially getting 3-deep coverage, a seam player, and one final defender to match the third receiver to either side (or cut any crossers). Because 2x2 is one-back and essentially a ‘spread’ set, the Rip/Liz check becomes the standard way to aggressively handle the two seam receivers. Instead of passing off receivers or spot-dropping, letting voids develop – this method ensures the routes will be accounted for while still avoiding the inflexibility of true man coverage.

How the remaining back will be accounted for is all that really differs from Cover 3. This also plays into how shallow crossers will be handled (with inside verticals compensated with Rip/Liz). Without the ability to funnel the back between two linebackers, you only have one backer (and lose the ability to ROBOT away inside routes). This essentially has the middle hole player assigned to aggressively match the back (who is #3 receiver to whichever side he releases).

2x2 out of a 3-deep concept (fire zone) will be handled simply by Rip/Liz in all cases. This remains true unless a receiver immediately breaks inside under 5 yards. With inside breaking routes, the defenders will not chase but alert the final 3rd player that he has a route approaching (“cut” as the hole defender). The final 3rd defender will receive an “UNDER” call from one of the outside defenders (an inside breaking route under 5 yards). This is a post-snap call on Rip/Liz to zone off into a 3 deep principle (#1 or #2 takes route inside).

Typically with a shallow, it is paired with a back flaring to the side of the field where the shallow originated to serve as an outlet receiver. This makes for an easy exchange, just like a “rat” call in Cover 1. The SCIF and final 3rd player just replace one another’s receiver, though the distribution remains consistent (the shallow becomes the 3rd route, the flare is the 2nd route, and the post is the 1st route in the distribution).

A more challenging route package for matching would feature the shallow to the same side as the flare. In this example, both SCIF players would carry #2 vertical with the Rip/Liz rules and the final 3rd player would pick up and carry the crosser after receiving the UNDER alert. With all threats leaving his area, the away-side corner would sink and high-leverage the dig route.

3 x 1

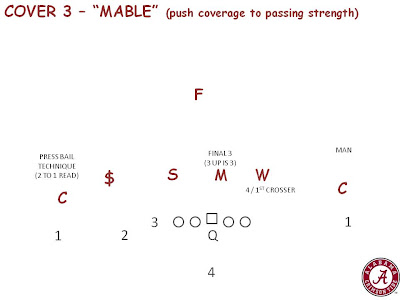

Trips formations can be a bit more challenging to the fire zone because it can immediately out-leverage defenders by alignment (3 receiver side). Even though it presents a horizontal stretch, the 3 receiver set can be handled using the same method as the zone-push concept, “Mable”. The first outside receiver would be manned by the corner. The second and third receivers will be (banjo) matched by the SCIF and final 3rd player underneath with the corner to trips manning on the #1 receiver. The away-side SCIF player would immediately look to match the back or whoever became the #4 receiver in the route distribution.

Here, just like in 2x2, the shallow by X precipitates an UNDER call by the corner letting the final 3rd player know he has a receiver crossing the formation (becoming the 3rd receiver / 1st receiver inside to trips) to cut. The away side corner would high-shoulder squeeze the shallow into the formation until picking up the (meshing) drag by Y. This leaves the away-side SCIF player free to jump the back releasing to his side.

The previous two examples showed #2 in the trips being the first underneath out route. What happens if #2 releases inside (such as with spacing shown here)? The H receiver would become the first receiver inside, with the Y being the first receiver outside. Since the H is no longer the #2 route in the distribution, he is passed off to the final 3rd player. The SCIF player matches the Y as the first of these two ‘outside’ underneath.

With empty, the only check required would to be ensure that the rush is coming away from the 3-man surface due to leverage issues. With two receivers away from trips essentially in man coverage and zoning to the trips, it would require the zone defenders to the trips side to be afforded the best possible positioning on the two inside receivers (just flipping where the overload is coming from). Just like against any trips set, the trips-side defenders would Mable (zone push) into the route dispersion. The away-side would aggressively man the remaining 2 receivers and retain the middle-of-the-field safety.

** PS **

The slot coverage post is coming. This pattern match post just happened to be ready first and I don’t want to sit on anything that could help.

Also, if you haven’t figured it out already, our former YouTube account that included many of the cut-ups featured in previous posts has been deleted by Google/NFL Properties. Hope you downloaded / picked up on those video illustrations while they were up.